Why This Matters (And Why You Should Care)

You’ve probably heard that “data is the new oil.” But here’s the problem: unlike oil, data comes with privacy strings attached. Every time a company collects your data to train a better AI model, they’re holding onto something that could leak, get hacked, or be misused.

Federated learning is the answer to a simple question: “Can we make AI smarter without hoarding everyone’s personal data?”

Spoiler: Yes. And it’s already happening on your phone right now.

This post is a deep dive into how federated learning actually works, the different flavors it comes in, the problems it creates, and the clever solutions researchers have built to fix them. Buckle up—this one’s detailed.

Part 1: How Federated Learning Actually Works (Under the Hood)

Let’s start with the fundamentals. I’m going to walk you through what happens during a typical federated learning training round, step by step.

The Players in the Game

Before we dive in, here are the main actors:

- Central Server – Coordinates everything, holds the global model

- Clients – Your phone, your laptop, a hospital’s server, etc. They have the data

- Global Model – The shared AI model everyone’s trying to improve

- Local Models – Temporary copies of the global model that train on each client

The Training Loop (Round by Round)

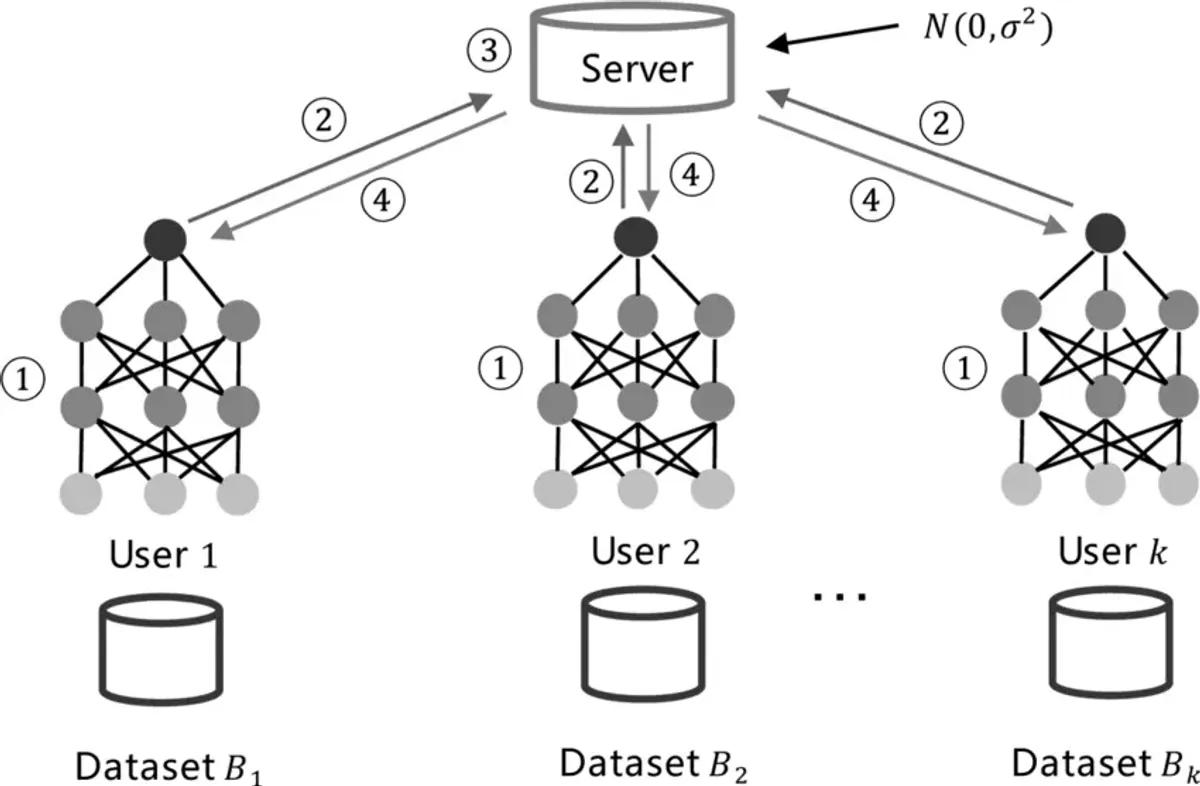

Here’s what a single “communication round” looks like:

Round 0: Initialization

The server creates a brand-new model (let’s say it’s a neural network for predicting the next word you’ll type). This model starts out dumb—it’s just random weights and biases. The server broadcasts this model to all participating clients.

Server → Client 1: "Here's the initial model"Server → Client 2: "Here's the initial model"Server → Client 3: "Here's the initial model"... (and so on for millions of devices)Note (What Gets Sent?)

The “model” being sent is just a bunch of numbers (the neural network’s weights and biases). It’s tiny compared to raw data—maybe a few megabytes. This is important because it means the communication overhead is low.

Round 1: Local Training

Each client now trains the model locally using only its own data. Your phone trains on your typing history. My phone trains on mine. A hospital trains on its patient data.

Here’s what happens on each device:

- Load the global model (the one the server just sent)

- Train for a few epochs using local data

- Forward pass: run inputs through the model

- Compute loss: how wrong was the prediction?

- Backward pass: adjust weights to reduce the loss

- Save the updated model weights

The key detail: The data never leaves the device. Only the model trains locally.

Example (Example: Your Phone)

Your phone has 10,000 text messages. It runs the model on batches of these messages, updating the weights after each batch. After 5 epochs, the model is slightly better at predicting your typing patterns. But the server never sees your messages—only the improved model weights.

Round 2: Upload Model Updates

Each client now sends its updated model weights back to the server.

Client 1 → Server: "Here's my improved model"Client 2 → Server: "Here's my improved model"Client 3 → Server: "Here's my improved model"Notice what’s NOT being sent:

- The raw data (your messages, health records, etc.)

- Individual data points

- Gradients (in basic federated learning)

What IS being sent:

- The model weights (just numbers)

The model weights are like a “summary” of what the client learned, without revealing the actual data.

Round 3: Aggregation (The Magic Step)

Now the server has a bunch of different models, each trained on different data. How do you combine them into one?

The most common method is Federated Averaging (FedAvg). Here’s the formula:

Where:

- = the new global model weights

- = number of clients

- = number of data samples client has

- = total samples across all clients

- = the weights from client

In plain English: Weighted average based on how much data each client has.

If Client 1 has 10,000 samples and Client 2 has 1,000 samples, Client 1’s model counts for 10× more in the final average.

Explanation (Why Weighted Average?)

If you averaged all models equally, a client with 10 data points would have the same influence as a client with 10,000. That’s unfair and statistically incorrect. Weighting by data size ensures each individual data point contributes equally to the global model.

Round 4: Broadcast the New Model

The server now has an improved global model. It sends this updated model back to all clients, and the process repeats.

Server → All Clients: "Here's the new, improved model"Over many rounds (say, 100 rounds), the global model gets better and better, even though the server never saw any raw data.

Visual Summary

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐│ FEDERATED LEARNING LOOP │└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

1. SERVER BROADCASTS MODEL ┌──────────┐ │ Server │ ──→ Model ──→ Client 1 │ │ ──→ Model ──→ Client 2 └──────────┘ ──→ Model ──→ Client 3

2. CLIENTS TRAIN LOCALLY (IN PARALLEL) Client 1: Train on local data → improved model_1 Client 2: Train on local data → improved model_2 Client 3: Train on local data → improved model_3

3. CLIENTS UPLOAD MODEL UPDATES Client 1 ──→ model_1 ──→ ┌──────────┐ Client 2 ──→ model_2 ──→ │ Server │ Client 3 ──→ model_3 ──→ └──────────┘

4. SERVER AGGREGATES (FedAvg) Global Model = weighted_avg(model_1, model_2, model_3)

5. REPEAT (go back to step 1)Part 2: Types of Federated Learning

Not all federated learning is the same. Depending on how the data is distributed across clients, we get different types.

1. Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL)

What it is: All clients have the same features but different samples.

Example: Multiple hospitals training a cancer detection model. All hospitals have the same type of data (patient age, tumor size, blood test results), but each hospital has different patients.

Hospital A: [Patient 1, Patient 2, Patient 3, ...]Hospital B: [Patient 50, Patient 51, Patient 52, ...]Hospital C: [Patient 100, Patient 101, Patient 102, ...]

All have same features: [age, tumor_size, blood_pressure, ...]Use Case: When organizations of the same type want to collaborate.

Example (Real-World Example)

Google’s Gboard keyboard uses horizontal federated learning. Every phone has the same features (text input), but different samples (your messages vs. my messages). All phones contribute to a global next-word prediction model.

2. Vertical Federated Learning (VFL)

What it is: Clients have the same samples but different features.

Example: A bank and an e-commerce company want to build a credit risk model. They share the same customers, but each has different data about them.

Bank: [Customer 1: credit_score, loan_history, ...]E-commerce: [Customer 1: purchase_history, browsing_data, ...]

Same customers, different featuresThe Challenge: How do you train a model when the data is split vertically across organizations?

The Solution: Use secure multi-party computation or homomorphic encryption to compute gradients without revealing features to each other.

Use Case: Cross-industry collaboration (bank + retailer, hospital + insurance).

3. Federated Transfer Learning (FTL)

What it is: Clients have different samples AND different features—almost no overlap at all.

Example: A Chinese e-commerce company and a European bank want to collaborate, but they have totally different customers and totally different data types.

The Solution: Use transfer learning techniques to find a shared representation space where both datasets can contribute.

Use Case: International collaborations, cross-domain learning.

Part 3: The Big Problems (And Why They’re Hard)

Federated learning sounds great in theory, but in practice, it’s a minefield of challenges. Let’s walk through the main ones.

Problem 1: Communication Overhead

The Issue: Training a model requires thousands of rounds. Each round involves uploading model weights from potentially millions of devices.

Why It’s Bad:

- Mobile devices have limited bandwidth

- Uploads cost money (data plans)

- Slow connections bottleneck the entire system

The Math: If you have 1 million clients and each uploads a 10 MB model every round, that’s 10 TB per round. Over 100 rounds, that’s 1 petabyte of data transferred.

Warning (Real-World Impact)

In Google’s federated learning experiments, communication costs were orders of magnitude higher than computation costs. Sending the model updates was more expensive than actually training them.

Problem 2: Statistical Heterogeneity (Non-IID Data)

The Issue: Clients don’t have identical data distributions. Your typing habits are different from mine. Hospital A treats cancer patients; Hospital B treats heart disease patients.

Why It’s Bad:

- Models trained on non-IID data can diverge instead of converge

- The global model might perform poorly on individual clients

- Some clients might “pull” the model in conflicting directions

Example:

Client 1 data: 90% cat images, 10% dog imagesClient 2 data: 10% cat images, 90% dog imagesClient 3 data: 50% cat images, 50% dog images

If we just average the models, the global model might be confused.This is called client drift—when local models drift away from the global optimum.

Definition (The IID Assumption)

IID = Independent and Identically Distributed. It means every client’s data comes from the same underlying distribution. In the real world, this almost never happens. Your Netflix viewing history is nothing like mine.

Problem 3: System Heterogeneity

The Issue: Devices have wildly different capabilities.

- A flagship phone from 2024 has a powerful GPU

- A budget phone from 2018 has a slow CPU

- Some clients have WiFi, others have spotty 3G

- Battery life varies

Why It’s Bad:

- Slow clients can delay the entire training round (stragglers)

- Some clients might drop out mid-training

- The server has to wait for everyone, or risk biasing the model

Example:

Fast Client: Finishes training in 10 secondsMedium Client: Finishes in 2 minutesSlow Client: Finishes in 10 minutes (or crashes)

If the server waits for everyone, the slow client bottlenecks everything.If the server doesn't wait, the slow client's contribution is lost.Problem 4: Privacy Attacks (Yes, Really)

Federated learning is designed for privacy, but it’s not foolproof. Attackers can still infer information from model updates.

Attack 1: Membership Inference

- Goal: Determine if a specific data point was in the training set

- Method: Analyze the model’s confidence on that data point

- Impact: “Was Alice in the training data?” → Privacy leak

Attack 2: Model Inversion

- Goal: Reconstruct training data from model weights

- Method: Use gradients to reverse-engineer inputs

- Impact: Recover actual images or text from the model

Attack 3: Data Poisoning

- Goal: Inject malicious data to corrupt the global model

- Method: A malicious client sends fake model updates

- Impact: The global model learns the wrong thing (or has a backdoor)

Important (Federated Learning ≠ Perfect Privacy)

Just because raw data isn’t shared doesn’t mean you’re 100% safe. Model weights can still leak information. This is why additional techniques like differential privacy and secure aggregation are needed.

Problem 5: Convergence is Slower

The Issue: Federated learning converges slower than centralized training.

Why?

- Clients train on different (non-IID) data

- Communication delays between rounds

- Clients might do different numbers of local epochs

Comparison:

| Metric | Centralized Learning | Federated Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Rounds to converge | 50 | 200+ |

| Time per round | Seconds | Minutes (waiting for clients) |

| Total time | Hours | Days |

For time-sensitive applications, this can be a dealbreaker.

Part 4: Solutions to the Problems

Researchers have developed clever solutions to tackle these challenges. Let’s go through them.

Solution 1: Reduce Communication Overhead

Problem: Too much data being transferred.

Solutions:

a) Model Compression

Instead of sending the full model, send a compressed version.

- Quantization: Reduce precision of weights (32-bit → 8-bit)

- Sparsification: Send only the top-k largest weights

- Gradient compression: Use sketching algorithms to compress gradients

Example: Original model: 100 MB Quantized model: 25 MB (75% reduction)

b) Fewer Communication Rounds

Train for more local epochs before uploading.

Instead of:

1 local epoch → upload → repeat 100 timesDo:

10 local epochs → upload → repeat 10 timesTrade-off: More local training can increase client drift.

c) Asynchronous Updates

Don’t wait for all clients. Let fast clients upload immediately.

Fast client uploads → server updates → broadcast to others(Don't wait for slow clients)Trade-off: Can introduce bias if slow clients are systematically different.

Warning (Compression Trade-offs)

Heavy compression can hurt model accuracy. You’re trading communication efficiency for precision. The key is finding the sweet spot where you save bandwidth without sacrificing too much performance.

Solution 2: Handle Non-IID Data

Problem: Clients have different data distributions.

Solutions:

a) FedProx (Federated Proximal)

Add a regularization term that prevents local models from drifting too far from the global model.

Loss function:

The second term is a “proximity” penalty. If your local model diverges too much from the global one, you pay a price.

b) FedAvg with Momentum

Use momentum-based optimization (like Adam or SGD with momentum) to smooth out the updates.

c) Personalization

Instead of a single global model, allow each client to have a slightly personalized version.

Global Model: 80% of the weightsLocal Model: 20% personalized to each clientThis way, the global model captures general patterns, but each client can still adapt to its unique data.

Example (Personalization Example)

A global keyboard model might know that “the” is a common word. But your personalized model knows you often type “btw” and “haha.” Best of both worlds.

Solution 3: Handle System Heterogeneity

Problem: Devices have different speeds and capabilities.

Solutions:

a) Client Selection

Don’t use all clients every round. Sample a random subset.

Round 1: Select 1,000 random clientsRound 2: Select a different 1,000 random clients...This avoids waiting for stragglers.

b) Adaptive Batch Sizes

Let each client choose its own batch size based on its hardware.

Powerful device: batch_size = 128Weak device: batch_size = 32The aggregation step accounts for this by weighting contributions fairly.

c) Deadline-Based Training

Set a time limit. Clients that finish within the deadline contribute; others are ignored for that round.

Deadline: 5 minutes

Fast Client: Finishes in 2 min → ✅ IncludedMedium Client: Finishes in 4 min → ✅ IncludedSlow Client: Still training at 5 min → ❌ SkippedTrade-off: Might introduce bias if slow clients are systematically different.

Solution 4: Defend Against Privacy Attacks

Problem: Model updates can leak information.

Solutions:

a) Differential Privacy

Add carefully calibrated noise to the model updates before sending them to the server.

True model update: [0.5, 0.3, 0.7, ...]Noisy update: [0.52, 0.28, 0.71, ...] (added Gaussian noise)The noise is small enough that it doesn’t hurt the model, but large enough that you can’t reverse-engineer individual data points.

The Math:

Where controls the privacy-accuracy trade-off.

Theorem (Differential Privacy Guarantees)

A mechanism is -differentially private if, for any two datasets differing in one data point, the probability distributions of the outputs are close. Smaller = stronger privacy, but more noise.

b) Secure Aggregation

Use cryptographic techniques so the server can compute the weighted average without seeing individual client updates.

How it works:

- Each client encrypts its model update

- The server computes the average of the encrypted updates

- The result is decrypted to reveal only the aggregate, not individual contributions

This is done using homomorphic encryption or secure multi-party computation (SMPC).

Example (Secure Aggregation in Action)

Imagine 3 clients:

- Client 1: update = 5 (encrypted)

- Client 2: update = 7 (encrypted)

- Client 3: update = 3 (encrypted)

The server computes: (5 + 7 + 3) / 3 = 5 (average)

But the server never learns that Client 1 contributed 5. It only learns the final average.

c) Byzantine-Robust Aggregation

Defend against malicious clients who send fake updates.

Krum Algorithm: Instead of averaging all updates, select the update that’s closest to the majority of other updates.

10 honest clients: Updates are similar1 malicious client: Update is wildly different

Krum selects the median update, ignoring the outlier.Solution 5: Speed Up Convergence

Problem: Federated learning is slow.

Solutions:

a) Better Optimizers

Use smarter optimization algorithms:

- FedAdam: Adaptive learning rates per client

- Scaffold: Variance reduction to correct for client drift

b) Pre-training

Start with a pre-trained model instead of random initialization.

Instead of: Random model → train from scratchDo: Pre-trained model (e.g., GPT-3) → fine-tuneThis drastically reduces the number of rounds needed.

c) Knowledge Distillation

Train a smaller “student” model using the global “teacher” model.

Large global model (100M parameters) → compress →Small local model (10M parameters)The small model is faster to train and transfer, but still captures most of the knowledge.

Part 5: Advanced Topics (For the Curious)

1. Cross-Silo vs. Cross-Device Federated Learning

Cross-Silo: Small number of powerful clients (e.g., hospitals, companies)

- Clients: 10-100

- Hardware: Data centers, servers

- Data: Large, high-quality datasets

- Use Case: Hospital collaborations, financial institutions

Cross-Device: Massive number of weak clients (e.g., phones, IoT devices)

- Clients: Millions

- Hardware: Mobile devices, low power

- Data: Small, noisy datasets

- Use Case: Keyboards, recommendation systems

Different challenges require different solutions.

2. Federated Learning with GANs

GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) in a federated setting are tricky because you have two models (Generator and Discriminator) that need to be synchronized.

Approach:

- Each client trains both Generator and Discriminator locally

- Upload both models to the server

- Server aggregates Generators separately from Discriminators

- Broadcast updated Generator and Discriminator back to clients

Challenge: GANs are notoriously unstable. Non-IID data makes it worse.

Note (Why GANs in Federated Learning?)

GANs can generate synthetic data that mimics real data without sharing the actual data. This is useful for data augmentation and privacy-preserving data sharing.

3. Federated Reinforcement Learning

Training RL agents in a federated setting (e.g., autonomous vehicles learning to drive).

Challenge: RL requires exploration, which is hard when you can’t share experiences directly.

Solution: Share policy gradients instead of experiences.

Agent 1: Learns from its environment → policy updateAgent 2: Learns from its environment → policy updateServer: Aggregates policy updates → global policy4. Incentive Mechanisms

Problem: Why would clients participate? Training costs battery, bandwidth, and computation.

Solutions:

- Monetary rewards: Pay clients for contributing

- Reputation systems: Clients earn reputation for high-quality contributions

- Service improvement: Better models = better user experience (implicit incentive)

Google’s Gboard doesn’t pay you, but you benefit from better predictions.

Part 6: Practical Considerations

When Should You Use Federated Learning?

Use federated learning if:

- Data is sensitive (health, finance, personal messages)

- Data is distributed across many sources

- Privacy regulations apply (GDPR, HIPAA)

- Centralization is expensive or impossible

Don’t use federated learning if:

- You control all the data

- Privacy isn’t a concern

- You need fast convergence

- Communication bandwidth is severely limited

Implementing Federated Learning

Frameworks:

- TensorFlow Federated (TFF): Google’s framework

- PySyft: Built on PyTorch, supports privacy techniques

- Flower: Lightweight, framework-agnostic

- FATE: Industrial-grade FL platform

Example (TensorFlow Federated):

import tensorflow_federated as tff

# Define modeldef model_fn(): return tff.learning.from_keras_model( keras_model=create_model(), input_spec=input_spec, loss=tf.keras.losses.SparseCategoricalCrossentropy(), metrics=[tf.keras.metrics.SparseCategoricalAccuracy()] )

# Build federated averaging processiterative_process = tff.learning.build_federated_averaging_process(model_fn)

# Trainstate = iterative_process.initialize()for round in range(num_rounds): state, metrics = iterative_process.next(state, federated_train_data) print(f'Round {round}, Metrics: {metrics}')Tip (Getting Started)

If you’re new to federated learning, start with TensorFlow Federated. It has great tutorials and handles most of the complexity for you. Once you’re comfortable, explore PySyft for more advanced privacy features.

Wrapping Up

Federated learning is a paradigm shift. Instead of “bring the data to the model,” it’s “bring the model to the data.” This flips the entire data pipeline on its head.

Is it perfect? No. Communication overhead is real. Non-IID data is a pain. Privacy attacks still exist. But the benefits—privacy, compliance, decentralization—are too big to ignore.

The next decade will see federated learning go from niche research to mainstream practice. And honestly? I’m here for it.

Summary (Final Thoughts)

Key Takeaways:

- Federated learning keeps data local, shares only model updates

- Three main types: Horizontal, Vertical, Transfer Learning

- Big challenges: Communication, non-IID data, heterogeneity, privacy attacks

- Solutions exist: Compression, FedProx, differential privacy, secure aggregation

- It’s already in production (Google, Apple, Tesla)

- The future is federated (probably)

Further Reading

Note (Papers Worth Reading)

- Original FedAvg Paper: “Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data” (McMahan et al., 2017)

- FedProx: “Federated Optimization in Heterogeneous Networks” (Li et al., 2020)

- Differential Privacy in FL: “Differentially Private Federated Learning” (Geyer et al., 2017)

- Privacy Attacks: “Deep Leakage from Gradients” (Zhu et al., 2019)

- Survey Paper: “Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning” (Kairouz et al., 2021)

Got questions? Spot an error? Want to argue about FedProx vs. Scaffold? Drop a mail—I’d love to hear from you.