Maps: The Foundation of Go

Maps are one of Go’s most useful and frequently used data structures. They’re everywhere: caching, tracking state, counting frequencies, storing configuration. Yet most developers never ask: how are they actually implemented?

Understanding Go’s map internals teaches you about:

- Hash functions and hash tables

- Collision resolution

- Memory layout and cache efficiency

- The evolution from simple implementations to optimized designs (Go 1.24)

This post explores all of it.

Part 1: Maps in Go — Basic Usage

Declaring and Using Maps

// Declare a map from string to float64var temperatures map[string]float64

// Initialize with maketemperatures = make(map[string]float64)

// Or declare and initialize togetherscores := map[string]int{"alice": 100, "bob": 85}

// Inserttemperatures["NYC"] = 72.5scores["charlie"] = 95

// Lookuptemp := temperatures["NYC"] // 72.5missing := temperatures["nowhere"] // 0 (zero value)temp, ok := temperatures["nowhere"] // 0, false (comma-ok)

// Deletedelete(temperatures, "NYC")

// Iteratefor city, temp := range temperatures { fmt.Printf("%s: %.1f°F\n", city, temp)}

// LengthnumCities := len(temperatures)

// Clear (Go 1.22+)clear(temperatures)Key Constraints

Keys must support the == operation:

// Valid key typesm1 := map[string]int{} // string ✓m2 := map[int]string{} // int ✓m3 := map[float64]bool{} // float64 ✓ (but risky due to floating point)

// Invalid key typesm4 := map[[]int]string{} // slices don't support ==m5 := map[map[string]int]bool{} // maps don't support ==m6 := map[func()]int{} // functions don't support ==

// Structs are OK if all fields support ==type Point struct { x, y int}m7 := map[Point]string{} // ✓ struct fields support ==Performance Expectations

All operations run in constant expected time:

m := make(map[string]float64)m["key"] = 3.14 // O(1) expectedval := m["key"] // O(1) expecteddelete(m, "key") // O(1) expected“Expected” is important. With adversarial input, worst case is O(n), but Go protects against this (more on that later).

Note

Go maps vs other languages:

- C++: Maps use ordered trees (O(log n)), but you can provide custom hash functions

- Java: You can define

hashCode()andequals() - Python: You can define

__hash__()and__eq__() - Go: No custom hash functions. Go handles hashing internally for you. This is both a limitation and a strength (prevents adversarial attacks)

Part 2: Why Maps Need Hash Functions

The Naive Approach: Linear Search

Imagine you implement a map as a simple array of key-value pairs:

type entry struct { k string v float64}

type SimpleMap []entry

func (m SimpleMap) Lookup(k string) float64 { for _, e := range m { if e.k == k { return e.v } } return 0}Problem: Every lookup scans the entire array. O(n) time.

With 1 million entries, each lookup does 500,000 comparisons on average. Unacceptable.

The Bucketing Idea

Instead of a linear array, split data into buckets:

Bucket A-F: alice, anna, bob, charlie, david, frankBucket G-L: grace, henry, julia, kimberly, leo, lisaBucket M-R: mike, nancy, oscar, paul, quinn, rachelBucket S-Z: sam, tom, ursula, victor, wendy, zoeTo lookup “alice”, only search Bucket A-F. Much faster!

Problem: Uneven distribution. What if all data happens to be in A-F?

Bucket A-F: alice, anna, bob, charlie, david, frank, grace, henry, iris, jessica, kevin, liam, mike, nancy, oscar, paul, quinn, rachel, sam, tom, ursula, victor, wendy, zoeBucket G-L: (empty)Bucket M-R: (empty)Bucket S-Z: (empty)You’re back to O(n) for that bucket.

The Solution: Hash Functions

Instead of bucketing by first letter, use a hash function that distributes keys uniformly:

bucket = hash(key) % numBucketsThe hash function maps any key to a bucket number. A good hash function ensures keys are spread evenly across buckets.

hash("alice") % 4 = 2 -> Bucket 2hash("bob") % 4 = 0 -> Bucket 0hash("charlie") % 4 = 3 -> Bucket 3hash("david") % 4 = 1 -> Bucket 1

Result: Keys are evenly distributed across all bucketsProperties of a Good Hash Function

Required for correctness:

- Deterministic:

hash(k1) == hash(k2)ifk1 == k2. Same input always produces same output.

Wanted for performance:

- Uniform: Each key has roughly equal probability of landing in any bucket.

P(hash(k) == b) ≈ 1/numBuckets - Fast: Computing

hash(k)must be quick.

Wanted for security:

- Adversary-resistant: Hard for an attacker to find many keys that hash to the same bucket (DoS attack).

Go’s hash functions are carefully tuned to meet all these properties. Users can’t define custom hash functions (preventing subtle bugs and security issues).

Note

Why Go doesn’t allow custom hash functions:

This decision prevents:

- Hash function bugs - Developers often write incorrect hash functions

- Adversarial attacks - If attacker can choose hash function, they can craft keys that all hash to same bucket, causing O(n) lookups

- Portability issues - Hash function changes across Go versions could break code

The trade-off: Less flexibility, but more safety and performance by default.

Part 3: The Original Map Implementation

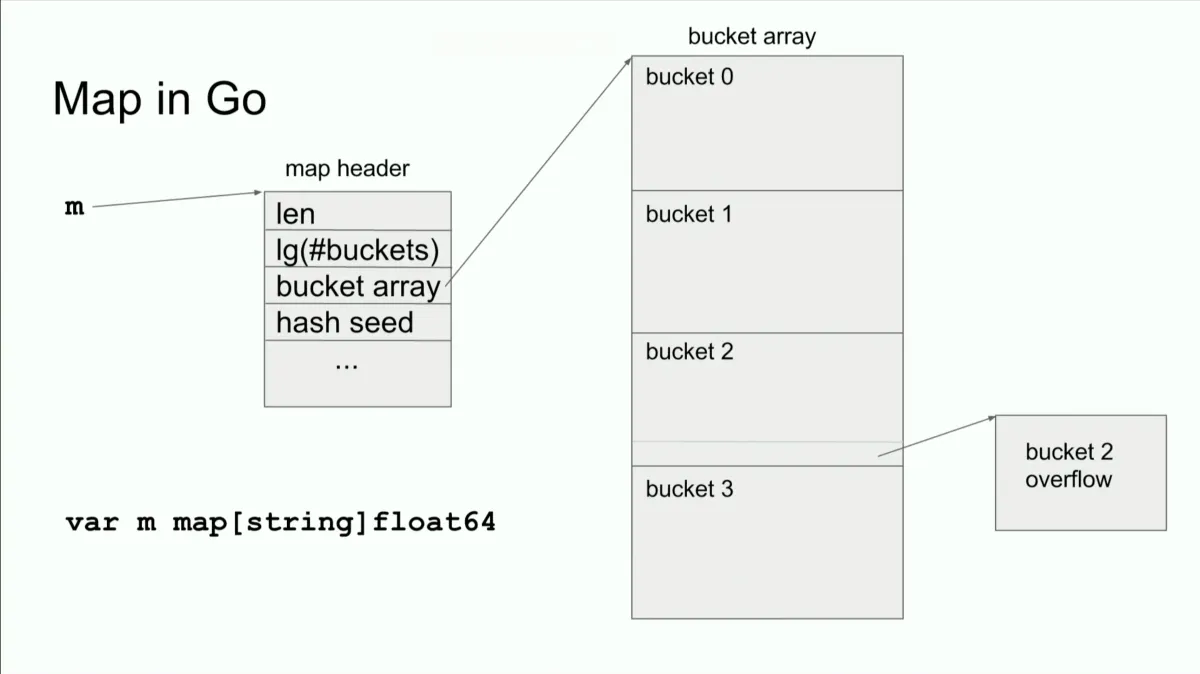

Map Header Metadata

In older Go, a map is a pointer to a map header:

// Conceptual representationtype mapHeader struct { count int // Number of entries flags uint8 // State flags B uint8 // log2(number of buckets). If B=5, numBuckets=32 noverflow uint16 // Approximate count of overflow buckets hash0 uint32 // Hash seed (for adversary resistance) buckets *[]*bucket // Array of buckets oldbuckets *[]*bucket // Old bucket array during growth nevacuate uintptr // Progress of evacuation extra *mapextra // Extra data}

type bucket struct { tophash [8]uint8 // Hashes of keys in this bucket keys [8]string // 8 keys values [8]float64 // 8 values overflow *bucket // Pointer to overflow bucket if full}Key insight: Each bucket can hold 8 entries. If more come, overflow buckets are created.

Lookup in the Original Implementation

// Conceptualfunc lookup(m *mapHeader, k string) float64 { // 1. Hash the key h := hash(k, m.hash0)

// 2. Get bucket index (take lower B bits) bucket_idx := h % (1 << m.B) // Same as h & ((1<<m.B) - 1)

// 3. Get hash prefix (top 8 bits) top := h >> 56 // Use highest 8 bits to quickly filter

// 4. Find the bucket b := m.buckets[bucket_idx]

// 5. Search within bucket for i := 0; i < 8; i++ { if b.tophash[i] == top && b.keys[i] == k { return b.values[i] } }

// 6. Check overflow buckets if any for b = b.overflow; b != nil; b = b.overflow { for i := 0; i < 8; i++ { if b.tophash[i] == top && b.keys[i] == k { return b.values[i] } } }

// Not found return 0}Optimizations:

- Top-hash (tophash): Store top 8 bits of hash. Quick rejection before comparing full keys.

- Buckets: Each bucket holds 8 entries, reducing indirection.

- Overflow buckets: Extra chains for collisions.

Growing the Map

When buckets get too full (~6.5 entries per bucket on average), allocate new buckets and grow:

func grow(m *mapHeader) { // 1. Allocate new bucket array (double the size) newNumBuckets := 1 << (m.B + 1) newBuckets := make([]*bucket, newNumBuckets)

// 2. Incrementally copy entries (during insert/delete) m.oldbuckets = m.buckets m.buckets = newBuckets m.B++ // New log2(numBuckets)

// 3. During subsequent operations, entries are re-hashed and moved // This is called "incremental evacuation"}The evacuation happens incrementally during inserts/deletes, avoiding a huge pause.

Part 4: Faking Generics in Go

The Generic Problem

In older Go, the lookup function would need to work for map[string]int, map[int]float64, etc.

Without generics, how?

// Pseudo-codefunc lookup(m map[K]V, k K) V { // What is K? What is V? // This doesn't work in Go}The Solution: unsafe.Pointer

Go fakes generics using unsafe.Pointer and type descriptors:

// Type descriptortype _type struct { size uintptr equal func(unsafe.Pointer, unsafe.Pointer) bool hash func(unsafe.Pointer, uintptr) uintptr // ... other fields}

type mapType struct { key *_type value *_type // ...}

// Generic-like lookup functionfunc lookup(t *mapType, m *mapHeader, k unsafe.Pointer) unsafe.Pointer { // Hash function from type descriptor h := t.key.hash(k, m.hash0) bucket_idx := h % (1 << m.B) top := uint8(h >> 56)

// ... search logic using unsafe pointers

return ptrToValue // unsafe.Pointer to the value}When you write v = m[k], the compiler generates:

pk := unsafe.Pointer(&k)pv := runtime.mapaccess1(typeOf(m), m, pk)v = *(*ValueType)(pv)The type descriptor tells the runtime how to hash and compare keys, even though the language doesn’t have explicit generics.

Note

Why unsafe.Pointer is safe here:

Unsafe code is dangerous, but Go runtime is a trusted component. It uses unsafe.Pointer carefully:

- All pointers are derived from real data

- Type descriptors are generated by the compiler, not user code

- The runtime validates operations

This is why you shouldn’t use unsafe.Pointer in user code, but the runtime can.

Part 5: Go 1.24 — Swiss Tables (Modern Implementation)

What Changed?

Go 1.24 completely rewrote maps using Swiss Tables, a design from Google’s Abseil library. The new implementation is dramatically faster.

The New Architecture: Groups of 8

Instead of individual buckets, maps now use groups of 8 key-value pairs:

┌─────────────────────────┐│ Control Word (64 bits) │ <- 8 bytes, one per slot├─────────────────────────┤│ Key 0 │ Value 0 ││ Key 1 │ Value 1 ││ Key 2 │ Value 2 ││ Key 3 │ Value 3 ││ Key 4 │ Value 4 ││ Key 5 │ Value 5 ││ Key 6 │ Value 6 ││ Key 7 │ Value 7 │└─────────────────────────┘Each slot’s status is tracked in the control word (8 bytes, 1 byte per slot).

Tables and Hashing

Maps consist of multiple tables, each containing multiple groups:

┌──────────────────────────┐│ Table 0 │├──────────────────────────┤│ [Group 0 with 8 slots] ││ [Group 1 with 8 slots] ││ [Group 2 with 8 slots] ││ ... │└──────────────────────────┘

┌──────────────────────────┐│ Table 1 │├──────────────────────────┤│ [Group 0 with 8 slots] ││ [Group 1 with 8 slots] ││ ... │└──────────────────────────┘When you hash a key, it gets split:

64-bit hash: |--------- 57 bits (h1) --------| | 7 bits (h2) | ↓ ↓ Selects table and group Matches against control wordh1 (57 bits): Determines which table and which group within that table.

h2 (7 bits): Matches against the control word to find candidate slots.

The Control Word

Each slot has a 1-byte status in the control word:

Empty: 10000000 (MSB = 1, others = 0)Deleted: 11111110 (MSB = 1, others = 1 except LSB)Occupied: 0xxxxxxx (MSB = 0, others = h2 bits)Why the MSB distinction?

The MSB (most significant bit) being 1 means “empty or deleted”. Being 0 means “occupied”. This allows quick filtering when scanning the control word.

Example: Lookup with h2 Matching

Suppose h2 = 0110111 (55 in decimal) and the control word is:

[01110110] [01011011] [00000000] [11111110] [01011011] [10101010] [11111111] [10000000] 0x76 0x5B 0x00 0xFE 0x5B 0xAA 0xFF 0x80 Slot 0 Slot 1 Slot 2 Slot 3 Slot 4 Slot 5 Slot 6 Slot 7Scanning for h2 = 01011011 (which is occupied), we find matches in slots 1 and 4:

- Slot 1: 0x5B matches h2

- Slot 4: 0x5B matches h2

The runtime then compares the actual key in each slot with the search key.

Lookup Algorithm

func lookup(m *mapHeader, k unsafe.Pointer) unsafe.Pointer { // 1. Hash the key h := hash(k)

// 2. Split hash into h1 and h2 h1 := h >> 7 // Top 57 bits h2 := h & 0x7F // Bottom 7 bits

// 3. Determine which table (based on leading bits of h1) tableIdx := h1 % len(tables) table := tables[tableIdx]

// 4. Calculate starting group (remaining h1 bits) groupIdx := (h1 >> bits_used_for_tables) % len(table)

// 5. Quadratic probing: check groups until found or empty found for step := 0; ; step++ { group := table[(groupIdx + step*step) % len(table)]

// 6. Scan control word for h2 matches for slot := 0; slot < 8; slot++ { if group.controlWord[slot] == h2 { // Found a match, compare actual keys if compareKeys(group.keys[slot], k) { return &group.values[slot] } } }

// 7. If we find an empty slot, key doesn't exist if group.controlWord[slot] == EMPTY { return nil } }}Quadratic Probing

When a group is full, instead of checking the next group (linear probing), check groups at quadratically increasing distances:

Full group at index 5Next check: index 5 + 1² = 6 (linear would check 6)Then check: index 5 + 2² = 9 (linear would check 7)Then check: index 5 + 3² = 14 (linear would check 8)Then check: index 5 + 4² = 21 (linear would check 9)Why quadratic instead of linear?

Linear probing causes clustering: many keys bunch together, slowing lookups. Quadratic probing spreads keys out, reducing congestion.

Insertion Algorithm

func insert(m *mapHeader, k, v unsafe.Pointer) { // Follow lookup probing sequence for step := 0; ; step++ { group := table[(groupIdx + step*step) % len(table)]

// Check if key already exists for slot := 0; slot < 8; slot++ { if group.controlWord[slot] == h2 && compareKeys(group.keys[slot], k) { // Update existing key group.values[slot] = v return } }

// Found empty slot, use it for slot := 0; slot < 8; slot++ { if group.controlWord[slot] == EMPTY { group.keys[slot] = k group.values[slot] = v group.controlWord[slot] = h2 return } }

// No empty slots, try to find deleted slot for slot := 0; slot < 8; slot++ { if group.controlWord[slot] == DELETED { group.keys[slot] = k group.values[slot] = v group.controlWord[slot] = h2 return } }

// Group full and no deleted slots, try next group // (continue loop with next step) }}Deletion Algorithm

func delete(m *mapHeader, k unsafe.Pointer) { // Find the key for step := 0; ; step++ { group := table[(groupIdx + step*step) % len(table)]

for slot := 0; slot < 8; slot++ { if group.controlWord[slot] == h2 && compareKeys(group.keys[slot], k) { // Key found, mark slot as deleted

// Check if group has empty slots hasEmpty := false for i := 0; i < 8; i++ { if group.controlWord[i] == EMPTY { hasEmpty = true break } }

if hasEmpty { // Mark as empty (to stop lookups early) group.controlWord[slot] = EMPTY } else { // Mark as deleted (to not stop lookups) group.controlWord[slot] = DELETED } return } }

// If we hit an empty slot, key doesn't exist if group.controlWord[slot] == EMPTY { return } }}Why distinguish between empty and deleted?

If you mark deleted slots as empty, lookups might stop prematurely:

Groups: [occupied, occupied, occupied, deleted, occupied] ↑Lookup for key at position 4 would stop herethinking the key doesn't exist, when it actually does.By marking deleted as “DELETED” (not empty), the lookup knows to keep searching.

Small Maps Optimization

For maps with ≤ 8 entries:

type mapHeader struct { count int flags uint8 // ... (for small maps) group group // Inline group, no tables}No tables, no probing. Just a single group with up to 8 slots. Linear scan is fast for 8 items.

As the map grows, the table system kicks in.

Map Growth

When load factor exceeds ~87% (occupied slots / total slots):

Load factor = occupied slots / total capacity

If load < 87%: Keep current layoutIf load >= 87%: If capacity <= 1024 slots: Double the capacity If capacity > 1024 slots: Split table into two tablesWhy not always double?

Doubling uses O(n log n) memory over a map’s lifetime. For large maps, splitting into multiple tables is more efficient:

Before split:tableIdx = h1 % 2 (using 1 bit of h1)0 → Table 01 → Table 1

After split (say Table 0 splits):tableIdx = h1 % 4 (using 2 bits of h1)00 → Table 0a (split from Table 0)01 → Table 0b (split from Table 0)10 → Table 111 → Table 1Keys that mapped to Table 0 now map to either Table 0a or 0b (based on the new bit). Keys that mapped to Table 1 still map to Table 1.

Note

Why Swiss Tables are faster:

- Compact layout: Data fits better in CPU caches. All 8 key-value pairs per group are contiguous.

- Control word scanning: One 8-byte comparison finds all h2 matches. Modern CPUs excel at this.

- Early termination: Finding an empty slot stops the lookup immediately.

- Quadratic probing: Distributes keys, reducing cluster conflicts.

- Separate tables: Multiple independent tables reduce contention in very large maps.

The result: Often 2-3x faster lookups than the original implementation.

Part 6: Real-World Implications

When to Use Maps

Good use cases:

- Caching: Fast lookup by ID, name, etc.

- Deduplication: Track seen items

- Counting: Frequency map

- Configuration: Settings by key

Avoid when:

- You need ordering (use

sort.Sliceon a slice of key-value pairs) - You need iteration order (maps are randomized)

- The key type is expensive to hash (though Go handles common types well)

Common Gotchas

Goroutine safety:

var m map[string]intgo func() { m["key"] = 1 }() // Race conditiongo func() { x := m["key"] }()Maps are not goroutine-safe. Use sync.Map or lock with sync.RWMutex.

Nil map:

var m map[string]intm["key"] = 1 // Panic: assignment to entry in nil map

m = make(map[string]int)m["key"] = 1 // ✓ OKAlways initialize with make() or a literal.

Deletion during iteration:

for k, v := range m { delete(m, k) // Undefined behavior (may skip or repeat)}Safer to collect keys first:

keys := make([]string, 0, len(m))for k := range m { keys = append(keys, k)}for _, k := range keys { delete(m, k) // ✓ Safe}Performance Tips

Pre-allocate if size is known:

// Bad: Triggers multiple growthsm := make(map[string]float64)for i := 0; i < 1000000; i++ { m[fmt.Sprintf("key%d", i)] = float64(i)}

// ✓ Good: Allocate upfrontm := make(map[string]float64, 1000000)for i := 0; i < 1000000; i++ { m[fmt.Sprintf("key%d", i)] = float64(i)}Key type matters:

// Slow: String hashing is expensivem := make(map[string]int)m["very_long_string_key_12345"] = 1

// ✓ Faster: Integer keys hash instantlym := make(map[int]int)m[12345] = 1Avoid pointer keys (usually):

// Usually bad: Pointer value changes if struct moves (in garbage collection)m := make(map[*Data]int)

// ✓ Better: Use a field value as keym := make(map[string]int)Part 7: Comparison with Other Languages

| Feature | Go | C++ | Java | Python |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Hash table | std::map (tree) or std::unordered_map | HashMap | dict |

| Custom hash | ❌ No | ✓ Yes | ✓ Yes | ✓ Yes |

| Ordered | ❌ No | ✓ (std::map) | ❌ No | ✓ Yes (3.7+) |

| Thread-safe | ❌ No | ❌ No | ❌ No | ✓ Yes (GIL) |

| Lookup time | O(1) expected | O(1) expected (hash) or O(log n) (tree) | O(1) expected | O(1) expected |

| Memory efficient | ✓ Very | ~ Medium | ~ Medium | ❌ Overhead |

Conclusion: Maps Are Sophisticated

Maps seem simple to use:

m[key] = valueBut beneath the surface:

- Hash functions distribute keys uniformly across buckets

- Collision resolution (buckets with overflow)

- Growth strategies (incremental evacuation)

- Generics simulation (type descriptors, unsafe.Pointer)

- Modern optimization (Swiss Tables with control words, quadratic probing, multiple tables)

Go 1.24’s rewrite to Swiss Tables is a testament to this: even after years, performance can improve through better algorithmic understanding.

The next time you use a map, you now know:

- How your key is hashed to find the bucket

- How collisions are handled

- Why insertion might be slower than lookup (growth)

- Why maps are fast and why order is random

Understanding these details makes you a better Go programmer.

Further Reading

Now go write some maps. You understand them better than 99% of developers.