Why Understanding Node.js Internals Matters

You write JavaScript. You run node server.js. Requests come in. Responses go out. But what actually happens in between?

Most developers treat Node.js like a black box. They know “Node.js is single-threaded” (which is kinda true, but also kinda wrong). They know “async/await makes things fast” (sometimes). They know “the event loop is important” (definitely true).

But do they understand it?

This post is a deep dive into the machinery. By the end, you’ll know:

- How JavaScript becomes machine code (V8 engine)

- How Node.js enables server-side JavaScript (libuv, C++ bindings)

- How thousands of requests are handled in a single-threaded runtime

- Why the event loop works the way it does

- How microtasks, macrotasks, and animation frames interact

- Real performance implications of understanding (or misunderstanding) these concepts

This isn’t theoretical fluff. Understanding this changes how you write code, debug issues, and optimize performance.

Let’s go deep.

Part 1: The Journey From JavaScript to Machine Code

The Gap: JavaScript Isn’t Native to the Processor

Here’s a fundamental truth: processors don’t understand JavaScript. They understand machine code (binary instructions).

When you write:

let x = 2 + 2;console.log(x);The CPU has no idea what this means. It needs to be converted to machine code it can execute.

Actually executed:MOV rax, 2 ; Move 2 into register raxADD rax, 2 ; Add 2 to rax...The Missing Link: JavaScript Engine

A JavaScript engine is the translator. It reads your JavaScript and converts it to machine code.

Examples of JavaScript engines:

- V8 – Used by Node.js and Chrome

- SpiderMonkey – Used by Firefox

- JavaScriptCore – Used by Safari

- QuickJS – Lightweight, embedded systems

The engine doesn’t care where the JavaScript runs. V8 can convert JavaScript to machine code anywhere—in a browser, on a server, on an IoT device.

Node.js: More Than Just V8

Here’s where most people get confused.

Misconception: “Node.js runs JavaScript”

Reality: V8 runs JavaScript. Node.js enables JavaScript to do server things.

V8 alone can execute JavaScript. But it can’t:

- Read files (

fs.readFile) - Create HTTP servers (

http.createServer) - Handle cryptography (

crypto.hash) - Listen on network sockets

- Manage memory efficiently for server workloads

These are system-level operations that require access to the operating system.

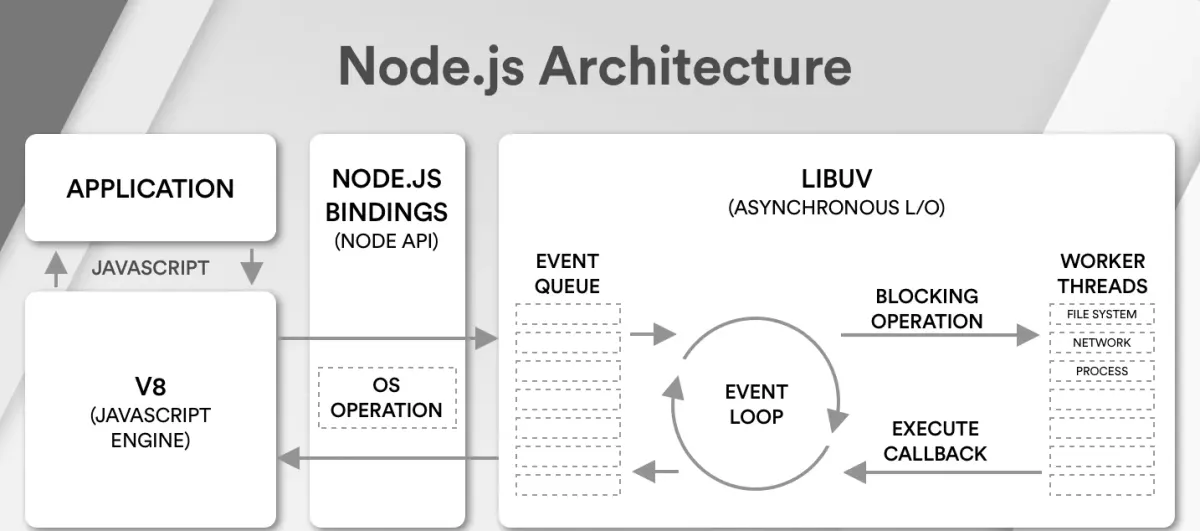

The Architecture: V8 + libuv + Node.js

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐│ Your JavaScript Code ││ (fs.readFile, http.listen) │└──────────────┬──────────────────────┘ │ ▼┌─────────────────────────────────────┐│ Node.js (Runtime) ││ - Provides fs, http, crypto, etc ││ - Bridges JS to OS operations ││ - Manages bindings between V8 & OS │└──────────────┬──────────────────────┘ │ ┌────────┴──────────┐ │ │ ▼ ▼ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ │ V8 │ │ libuv │ │(Execute) │ │(Schedule)│ └──────────┘ └──────────┘ │ │ └────────┬──────────┘ │ ▼ ┌──────────────────┐ │ Operating System│ │ (Linux/macOS/ │ │ Windows) │ └──────────────────┘C++ Bindings: The Bridge

Node.js itself is written in both JavaScript and C++.

When you call fs.readFile():

- JavaScript code calls the function

- Node.js has a C++ binding that wraps the actual file reading

- The C++ code uses OS system calls to read the file

- Results are marshaled back to JavaScript types (V8 objects)

// What you write (JavaScript)fs.readFile('file.txt', (err, data) => { console.log(data);});

// What happens internally (C++)// V8 converts JS objects to C++ objects// OS performs the actual file I/O// Results converted back to V8 objects// Callback is queued for later executionThis is why Node.js can do “system” things—it’s not actually JavaScript doing them. It’s C++ calling OS APIs, and JavaScript is just orchestrating it.

Note

Why this matters: Understanding this architecture explains why some operations are “async” (delegated to OS) and why JavaScript on its own can’t do these things. V8 is powerful, but it’s not magical. It still needs an operating system to do real work.

Part 2: Threads and Processes (The Myth of “Single-Threaded”)

What Does “Single-Threaded” Actually Mean?

You’ve heard this: “Node.js is single-threaded.”

This is simultaneously true and misleading.

Processes and Threads: Fundamentals

Process:

- Fundamental unit of execution on the OS

- Has its own memory space, registers, file descriptors

- Isolated from other processes

- Example: When you run

node server.js, you create one process

Thread:

- Lightweight unit of execution within a process

- Shares memory with other threads in the same process

- Can run in parallel (on multi-core systems)

- Context switching between threads has lower overhead than between processes

CPU Cores:

- A machine with 8 cores can execute 8 threads simultaneously

- More threads exist than cores (OS scheduler handles this)

- Context switching between threads is fast (microseconds)

Node.js: Single Main Thread, But Not Really Single-Threaded

When you run:

node server.jsOne primary thread is created—the one that executes your JavaScript code. This thread runs the V8 engine.

OS: "Node.js process spawned on Core 1"V8 + Event Loop: Running on Core 1JavaScript: Executing on Core 1This is why it’s “single-threaded.”

But here’s the twist: OS operations are not single-threaded.

When you call an async operation like fs.readFile():

fs.readFile('large-file.txt', (err, data) => { console.log('File read complete');});console.log('File read requested');Output:

File read requestedFile read completeWhat’s actually happening:

- JavaScript calls

fs.readFile() - Node.js delegates to the OS: “Please read this file”

- OS reads the file on a different core (not blocked on your main thread)

- OS signals back: “File is ready”

- Callback is executed on the main thread

Time: 0ms - Main thread: fs.readFile() calledTime: 0ms - Node.js: "OS, read this file" (delegates to Core 2)Time: 0ms - Main thread: Continues executing (not blocked)Time: 15ms - Core 2: Finishes reading fileTime: 15ms - Main thread: Executes callback (back on Core 1)So is Node.js single-threaded?

- Your JavaScript code? Yes, runs on one thread.

- The underlying system? No, OS can parallelize I/O across multiple cores.

- The result? You get concurrency (handling many requests) without explicit multithreading.

Note

Common Misconception: “Node.js is single-threaded so it can’t do CPU-heavy work efficiently.”

Reality: Node.js is single-threaded for JavaScript execution, but offloads I/O to the OS. However, if you do CPU-heavy work in JavaScript (loops, calculations), it WILL block the main thread. That’s a problem.

Part 3: Thread Pools and CPU-Intensive Operations

The Thread Pool Problem

Some operations can’t be delegated to the OS easily. Example: password hashing with bcrypt.

const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');const http = require('http');

http.createServer((req, res) => { bcrypt.hash('password123', 10).then((hash) => { res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' }); res.write(hash); res.end(); });}).listen(3000);Bcrypt needs to do heavy CPU computation (iteratively hashing many times). The OS can’t do this for you—you need to actually run the algorithm.

But you can’t do it on the main thread—it would block all requests.

Solution: Thread Pool

libuv’s Thread Pool

libuv (the library that manages concurrency in Node.js) maintains a thread pool.

By default, it has 4 threads. You can configure this:

UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE=8 node server.jsWhen you call bcrypt.hash():

- Main thread receives request

- Bcrypt (C++ binding) requests a thread from libuv’s pool

- One of the 4 pool threads executes the hashing

- Main thread continues handling other requests

- When hashing completes, callback is queued

- Main thread executes callback and sends response

Request 1 → bcrypt.hash() → Thread 1 (hashing password1)Request 2 → bcrypt.hash() → Thread 2 (hashing password2)Request 3 → bcrypt.hash() → Thread 3 (hashing password3)Request 4 → bcrypt.hash() → Thread 4 (hashing password4)Request 5 → bcrypt.hash() → WAIT (all threads busy)Measuring Thread Pool Impact

Let’s benchmark. Create this server:

const http = require('http');const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

http.createServer((req, res) => { bcrypt.hash('codedamn-forever', 10).then((hash) => { res.writeHead(200, { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain' }); res.write(hash); res.end(); });}).listen(3000);Test with Apache Bench:

ab -n 1000 -c 100 http://localhost:3000/Results with different UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE:

| Thread Pool Size | Requests/sec |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~1030 |

| 2 | ~2000 |

| 3 | ~2900 |

| 4 (default) | ~3600 |

| 8 | ~3600 |

Why does it plateau at 4?

Because this machine has 4 CPU cores. Beyond 4 threads, you’re not gaining parallelism—you’re just context-switching, which wastes CPU cycles.

Optimal Thread Pool Size

Rule of thumb: Match thread pool size to logical CPU cores, maybe slightly higher (10-20%) for overhead.

const os = require('os');const optimalThreadPoolSize = os.cpus().length;

process.env.UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE = optimalThreadPoolSize;Important: Some CPUs have hyperthreading. A 4-core CPU with hyperthreading shows as 8 logical cores:

$ sysctl -n hw.ncpu8 # 4 physical cores × 2 threads per coreIn this case, you can slightly benefit from 6-8 threads (accounting for context switching overhead).

But never blindly increase it. More threads = more memory used, more context switching overhead. The benefits plateau quickly.

Note

Why this matters: If you’re running CPU-heavy operations in Node.js (image processing, crypto, compression), thread pool size directly affects throughput. Understanding this lets you tune performance appropriately.

Part 4: The Event Loop (The Core of Node.js)

What Is the Event Loop?

The event loop is a loop that runs in Node.js, constantly asking: “Is there anything to do?”

It’s not mysterious magic. It’s just a loop:

// Pseudo-code: This is roughly what libuv doeswhile (eventLoop.waitForTask()) { // Execute all synchronous code // Execute ready callbacks // Wait for I/O // Check timers // Repeat}Phases of the Event Loop

The event loop has distinct phases. Each phase handles different types of tasks.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Event Loop Phases │├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤│ ││ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ││ │ 1. timers: Execute setInterval/setTimeout callbacks │ ││ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ││ ↓ ││ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ││ │ 2. pending callbacks: Execute I/O callbacks │ ││ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ││ ↓ ││ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ││ │ 3. idle, prepare: Internal use (skip this) │ ││ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ││ ↓ ││ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ││ │ 4. poll: Wait for I/O events, execute I/O callbacks │ ││ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ││ ↓ ││ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ││ │ 5. check: Execute setImmediate callbacks │ ││ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ││ ↓ ││ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ ││ │ 6. close: Execute close callbacks │ ││ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ ││ ↓ ││ (Back to timers phase) ││ │└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘Phase 1: Timers

Execute callbacks scheduled with setTimeout() and setInterval() whose timers have expired.

setTimeout(() => console.log('Timeout expired'), 100);// When 100ms have passed, callback is executed in timers phasePhase 2: Pending Callbacks

Execute I/O callbacks that were deferred (system errors from previous cycles).

Phase 4: Poll (The Most Important)

This is where most of the action happens. The event loop:

- Checks if there are any pending I/O operations (file reads, network requests, database queries)

- If yes, waits for them to complete

- As they complete, executes their callbacks

fs.readFile('file.txt', (err, data) => { console.log('File read complete');});// When file read completes, callback executes during poll phaseIf there’s nothing to wait for, it moves to the next phase.

Phase 5: Check (setImmediate)

Execute callbacks scheduled with setImmediate(). These are higher priority than timers.

setImmediate(() => console.log('Immediate'));// Executes during check phasePhase 6: Close

Execute close callbacks for sockets, streams, etc.

Microtasks: The Hidden Phase

There’s actually a phase we haven’t mentioned—and it’s the most important: Microtask Phase.

Microtasks are not part of the event loop phases. They execute between every phase.

┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Phase 1: Timers │└───────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓ (All microtasks execute here)┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Phase 2: Pending Callbacks │└───────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓ (All microtasks execute here)┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Phase 4: Poll │└───────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓ (All microtasks execute here)... and so onWhat are microtasks?

- Promises (

.then(),.catch()) queueMicrotask()MutationObserver(browser)process.nextTick()(Node.js special)

Example:

setTimeout(() => console.log('Timer'), 0);Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('Promise'));

// Output:// Promise// TimerWhy? Promise goes to microtask queue. Timer goes to macrotask queue. Microtasks execute first.

Note

Critical misconception: “setImmediate runs immediately after the current code.”

Reality: setImmediate runs during the check phase, which is AFTER the poll phase. If there’s I/O waiting in the poll phase, setImmediate waits. Use process.nextTick() if you need something to run on the next iteration of the event loop (but not after I/O is polled).

Part 5: Understanding Execution Order (The Complete Picture)

Let’s trace through a complex example to see exactly what happens and in what order.

Example: Multiple Operations

console.log('1: Synchronous start');

setTimeout(() => { console.log('2: setTimeout 1'); Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('3: Promise inside setTimeout'));}, 0);

Promise.resolve() .then(() => { console.log('4: Promise 1'); setTimeout(() => console.log('5: setTimeout inside Promise'), 0); }) .then(() => console.log('6: Promise 2'));

console.log('7: Synchronous end');Expected output:

1: Synchronous start7: Synchronous end4: Promise 16: Promise 22: setTimeout 13: Promise inside setTimeout5: setTimeout inside PromiseLet’s trace it:

-

Synchronous code runs first

- Logs “1: Synchronous start”

- setTimeout is scheduled → goes to timer queue

- Promise.resolve().then() is scheduled → goes to microtask queue

- Logs “7: Synchronous end”

-

Event loop: Microtask phase (before any event loop phases)

- Executes first Promise → logs “4: Promise 1”

- Schedules setTimeout inside Promise → goes to timer queue

- Executes second Promise → logs “6: Promise 2”

-

Event loop: Timers phase (first phase)

- Executes first setTimeout → logs “2: setTimeout 1”

- Schedules Promise inside setTimeout → goes to microtask queue

-

Event loop: Microtask phase again (between phases)

- Executes Promise inside setTimeout → logs “3: Promise inside setTimeout”

-

Event loop: Timers phase again (cycles back)

- Executes setTimeout scheduled from Promise → logs “5: setTimeout inside Promise”

The Rule: Execution Order

Remember this simple rule:

Sync → Microtasks → Timer → Microtasks → I/O → Microtasks → …

Or more formally:

1. Execute all synchronous code in the call stack2. Call stack is empty → check microtask queue (exhaust it completely)3. Move to next event loop phase (timers, poll, etc.)4. After each phase → check microtask queue again (exhaust it)5. Repeat until all queues are emptyReal-World Complexity: The RAF Queue

In browsers, there’s another queue: Animation Frame Queue (via requestAnimationFrame).

It executes differently in Node.js vs browsers:

Browser:

Microtasks → Timers → Microtasks → RAF (at screen refresh, ~60Hz) → RepaintNode.js:

Microtasks → Timers → Microtasks → I/O → Microtasks → ...(No repaint phase, so RAF doesn't exist)In Node.js, setImmediate acts similar to browser’s requestAnimationFrame in concept (check phase), but RAF-specific behavior doesn’t apply.

Part 6: Practical Examples and Tracing

Example 1: The Classic Interview Question

console.log('start');

setTimeout(() => { console.log('setTimeout');}, 0);

Promise.resolve() .then(() => { console.log('promise'); });

console.log('end');Output:

startendpromisesetTimeoutWhy?

- Sync code runs: “start”, “end”

- Microtasks: Promise.then() → “promise”

- Timers: setTimeout → “setTimeout”

Example 2: Nested Promises and Timers

Promise.resolve() .then(() => { console.log('Promise 1'); setTimeout(() => console.log('Timer in Promise'), 0); }) .then(() => { console.log('Promise 2'); });

setTimeout(() => { console.log('Timer 1'); Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('Promise in Timer'));}, 0);

setTimeout(() => console.log('Timer 2'), 0);

console.log('Sync');Output:

SyncPromise 1Promise 2Timer 1Promise in TimerTimer 2Timer in PromiseTrace:

- Sync: “Sync”

- Microtasks: “Promise 1”, “Promise 2”

- Timers (first): “Timer 1”

- Microtasks: “Promise in Timer”

- Timers (second): “Timer 2”

- Timers (third, from Promise): “Timer in Promise”

Example 3: Understanding Microtask Queue Exhaustion

Promise.resolve().then(() => { console.log('M1'); Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('M1.1'));});

Promise.resolve().then(() => { console.log('M2'); Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('M2.1'));});

setTimeout(() => console.log('T1'), 0);Output:

M1M2M1.1M2.1T1Why? The microtask queue is exhausted completely before moving to timers:

- M1 executes, schedules M1.1

- M2 executes, schedules M2.1

- M1.1 executes

- M2.1 executes

- Now microtask queue is empty → move to timers

- T1 executes

Note

Why this matters: Microtask queue exhaustion is critical for understanding performance. If you have many promises chained, they all execute in a tight loop before any timers/I/O. This can cause “microtask starvation” where I/O is delayed.

Part 7: The Event Loop in the Browser

Node.js internals are similar to browsers, but with key differences.

Browser Event Loop

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Synchronous Code (Call Stack) │└──────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Microtask Queue (Promises, queueMicro) │└──────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Macrotask/Task Queue (setTimeout, etc) │└──────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Animation Frame Queue (requestAnimFrame) │└──────────────────────────────────────────┘ ↓┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Repaint & Layout │└──────────────────────────────────────────┘In the browser, requestAnimationFrame has special treatment—it’s guaranteed to run before the next repaint (typically 60 times per second for a 60Hz screen).

Node.js vs Browser: Key Differences

| Aspect | Node.js | Browser |

|---|---|---|

| Phases | 6 phases (timers, pending, poll, check, close) | Simpler: task → microtask → repaint |

| RAF | Not applicable (no UI rendering) | Runs before repaint, ~60Hz |

| setTimeout | In timers phase | In task queue |

| setImmediate | In check phase | Not available |

| process.nextTick | Special: runs after current phase | Not available |

| Repaint | N/A | Happens after microtasks and RAF |

Example: RAF is Slower Than setTimeout in Browsers

In a browser:

<div id="counter1"></div><div id="counter2"></div>

<script>let count1 = 0, count2 = 0;

function countWithSetTimeout() { count1++; document.getElementById('counter1').textContent = count1;

if (count1 < 1000) { setTimeout(countWithSetTimeout, 0); }}

function countWithRAF() { count2++; document.getElementById('counter2').textContent = count2;

if (count2 < 1000) { requestAnimationFrame(countWithRAF); }}

countWithSetTimeout();countWithRAF();</script>Result: setTimeout counter reaches 1000 much faster than RAF counter.

Why? setTimeout can execute many times per frame (every event loop cycle), but RAF only executes once per frame (~16.67ms at 60Hz).

This is why RAF is for animations (you don’t want to animate faster than the display can show), but setTimeout is for rapid callbacks.

Part 8: Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Pitfall 1: Blocking the Event Loop

const http = require('http');

http.createServer((req, res) => { // Heavy computation let sum = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 1000000000; i++) { sum += i; }

res.writeHead(200); res.end('Done');}).listen(3000);Problem: While the loop executes, no other requests can be processed. They queue up.

Solution 1: Break it into chunks with setImmediate

http.createServer((req, res) => { let sum = 0; let i = 0; const target = 1000000000;

function compute() { const chunkSize = 10000000; const end = Math.min(i + chunkSize, target);

for (; i < end; i++) { sum += i; }

if (i < target) { setImmediate(compute); // Yield to event loop } else { res.writeHead(200); res.end(`Sum: ${sum}`); } }

compute();}).listen(3000);Solution 2: Use Worker Threads

const { Worker } = require('worker_threads');

http.createServer((req, res) => { const worker = new Worker('./compute.js');

worker.on('message', (sum) => { res.writeHead(200); res.end(`Sum: ${sum}`); });}).listen(3000);Pitfall 2: Microtask Starvation

function starveMacrotasks() { Promise.resolve().then(() => { console.log('Microtask'); starveMacrotasks(); // Queue another promise });}

starveMacrotasks();

setTimeout(() => console.log('Macrotask (never logs!)'), 0);Problem: Promises keep getting queued faster than the event loop can process timers. The setTimeout callback never runs.

Solution: Be aware that microtasks have priority. Avoid infinite promise chains.

Pitfall 3: Misunderstanding setTimeout(0)

setTimeout(() => console.log('This is NOT immediate'), 0);Common misconception: “This runs immediately after the current code.”

Reality: It’s scheduled for the next timers phase, which might be 10-100ms later depending on:

- How many microtasks are pending

- How many other timers are scheduled

- System load

setTimeout uses the browser/Node’s timer implementation, which isn’t precise for small delays.

Solution: Use process.nextTick() if you need something after the current operation:

process.nextTick(() => console.log('Runs after current operation'));Or use setImmediate() if you need to defer to the next event loop iteration:

setImmediate(() => console.log('Runs in check phase'));Pitfall 4: Not Handling Backpressure in Streams

const fs = require('fs');

const readable = fs.createReadStream('huge-file.txt');const writable = fs.createWriteStream('output.txt');

readable.on('data', (chunk) => { writable.write(chunk);});Problem: If the readable stream is faster than the writable stream, chunks queue up in memory. This can crash your process.

Solution: Use pipe() which handles backpressure automatically

readable.pipe(writable);Or manually handle backpressure:

readable.on('data', (chunk) => { const canContinue = writable.write(chunk);

if (!canContinue) { readable.pause(); // Stop reading }});

writable.on('drain', () => { readable.resume(); // Resume reading});Note

Critical: Understanding the event loop isn’t just academic. It directly affects whether your application is fast or slow, responsive or sluggish. Blocking the event loop is one of the most common performance mistakes in Node.js.

Part 9: Performance Implications

Real-World Impact: Throughput

Let’s measure how event loop understanding impacts actual performance.

Scenario: HTTP server that hashes passwords

const http = require('http');const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

http.createServer((req, res) => { bcrypt.hash('password', 10).then((hash) => { res.writeHead(200); res.end(hash); });}).listen(3000);With UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE=4 (default on 4-core machine):

- Throughput: ~3600 requests/second

- Average latency: ~25ms

With blocking code instead:

http.createServer((req, res) => { // Simulating CPU-heavy work let sum = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 100000000; i++) { sum += i; }

res.writeHead(200); res.end('Done');}).listen(3000);Result:

- Throughput: ~50 requests/second (72x slower!)

- Average latency: ~1000ms

Lesson: Understanding how to properly delegate work (to thread pools, to the OS, to worker threads) is critical for performance.

Latency Distribution Matters

Looking at average throughput isn’t enough. Latency distribution matters:

| Approach | p50 | p95 | p99 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Async bcrypt | 20ms | 35ms | 45ms | 60ms |

| CPU blocking | 500ms | 1000ms | 1500ms | 2000ms |

p95 = 95th percentile means 95% of requests are that fast or faster.

With blocking code, even 95% of users get a terrible experience (1000ms latency).

This is why understanding the event loop and async patterns is essential. Your users notice p95 latency way more than average latency.

Part 10: Debugging Event Loop Issues

Tool 1: process.cpuUsage()

Detect if the event loop is blocked:

const http = require('http');

setInterval(() => { const usage = process.cpuUsage(); console.log(`User CPU: ${usage.user}μs, System CPU: ${usage.system}μs`);}, 1000);

http.createServer((req, res) => { // Simulate work let sum = 0; for (let i = 0; i < 100000000; i++) { sum += i; }

res.end('Done');}).listen(3000);If CPU usage stays high but you’re not doing explicit work, the event loop is blocked.

Tool 2: Node’s —inspect Flag

node --inspect server.jsOpen chrome://inspect in Chrome DevTools. You can see:

- Timeline of event loop execution

- Where time is being spent

- Which callbacks are slow

Tool 3: Custom Event Loop Lag Monitoring

const lagThreshold = 100; // mslet lastCheck = Date.now();

setInterval(() => { const now = Date.now(); const lag = now - lastCheck - 100; // Expected 100ms interval

if (lag > lagThreshold) { console.warn(`Event loop lag detected: ${lag}ms`); }

lastCheck = now;}, 100);This detects if the event loop is delayed (lag) beyond expected intervals.

Tool 4: Flamegraph Analysis

Use tools like 0x or clinic.js:

npm install -g 0x

0x server.js# Test your server...# Ctrl+C to stop# Opens an interactive flamegraphShows exactly where CPU time is spent.

Part 11: Node.js Internals vs JavaScript in Browsers

The Fundamental Difference

Browser:

Window Object → Browser APIs (DOM, fetch, setTimeout) → V8 EngineNode.js:

Global Object → Node APIs (fs, http, crypto) → V8 EngineBoth use V8, but different APIs are available.

// Browserconsole.log(typeof window); // 'object'console.log(typeof document); // 'object'

// Node.jsconsole.log(typeof window); // 'undefined'console.log(typeof document); // 'undefined'console.log(typeof module); // 'object'How APIs are Implemented

Browser: JavaScript handles some DOM APIs, but relies on the browser’s C++ engine for the actual DOM tree.

Node.js: Node.js handles some logic (JavaScript), but relies on C++ bindings to the OS for I/O.

Both follow the same pattern:

High-level API (JS) → Binding Layer (C++) → Lower-level system (Browser DOM / OS)Node.js Module System vs ES6 Modules

Node.js traditionally uses CommonJS:

const fs = require('fs');module.exports = { ... };This is different from browser ES6 modules:

import fs from 'fs';export { ... };Node.js now supports both, but they have different module resolution algorithms.

Key difference: CommonJS is synchronous. Require a module, it executes immediately. ES6 modules are asynchronous.

Part 12: The C++ Layer: Why It Matters

Why Some Things Are Faster in C++

// JavaScript: Fast, but not fastestconst result = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].map(x => x * 2);

// C++: Faster for large datasets// Native code compiled to machine code directly// No type checking overhead// Direct memory managementFor operations like:

- JSON parsing (large files)

- Cryptographic hashing

- Image processing

- Database queries

C++ is often significantly faster.

V8 Data Types in C++

When JavaScript interacts with C++, values are converted:

// JavaScriptlet obj = { name: 'John', age: 30 };callCppFunction(obj);

// C++void callCppFunction(const v8::Local<v8::Object>& obj) { v8::String::Utf8Value name(isolate, obj->Get(context, key).ToLocalChecked()); int age = obj->Get(context, key2).ToLocalChecked()->Int32Value(context).FromJust();}This conversion has overhead. For simple operations, it might be slower than pure JavaScript.

Writing Native Modules

Developers can write native modules to speed up critical paths:

// example.cc (C++)#include <node.h>using namespace v8;

void Add(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) { Isolate* isolate = args.GetIsolate();

double a = args[0]->NumberValue(isolate->GetCurrentContext()).FromJust(); double b = args[1]->NumberValue(isolate->GetCurrentContext()).FromJust();

Local<Number> sum = Number::New(isolate, a + b); args.GetReturnValue().Set(sum);}

void init(Local<Object> exports) { NODE_SET_METHOD(exports, "add", Add);}

NODE_MODULE(example, init);Compiled to a .node binary and imported:

const addon = require('./build/Release/example.node');console.log(addon.add(5, 3)); // 8This is used by libraries like bcrypt, node-sass, sharp (image processing).

Part 13: The Future: Deno, Bun, and Alternatives

Node.js isn’t the only JavaScript runtime. There are alternatives with different design choices.

Deno

Created by Node.js’s original author, Deno rethinks JavaScript runtime design:

// Deno: More secure, different module systemimport { serve } from "https://deno.land/std@0.208.0/http/server.ts";

serve(() => new Response("Hello"), { port: 3000 });Key differences:

- Uses TypeScript by default

- URL-based module imports (no node_modules)

- Permissions model (ask for file access, network access, etc.)

- Simpler codebase than Node.js

Bun

A newer runtime focused on performance:

// Bun: Fast bundler and runtimeBun.serve({ fetch() { return new Response("Hello"); },});Key advantages:

- Faster startup time

- Integrated bundler

- Native support for TypeScript, JSX

- Drop-in Node.js compatibility (for most code)

Comparing Runtimes

| Feature | Node.js | Deno | Bun |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | Very mature (10+ years) | Growing | Early stage |

| Package ecosystem | npm (largest) | esm.sh, deno.land | npm compatible |

| TypeScript support | Via tools (ts-node) | Built-in | Built-in |

| Performance | Good | Similar | Faster startup |

| Enterprise adoption | Ubiquitous | Growing | Emerging |

For production systems, Node.js remains the most stable choice. But the alternatives show where the ecosystem might evolve.

Conclusion: Putting It All Together

Let’s recap the journey from your JavaScript code to machine code:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐│ Your JavaScript Code ││ const x = await fs.readFile(...) │└──────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────┘ │ ▼ ┌──────────────────────────────────────┐ │ Node.js Runtime Environment │ │ - C++ bindings to OS APIs │ │ - Event loop management │ │ - libuv for concurrency │ └──────────────────────────────────────┘ │ ┌─────────────────┼─────────────────┐ │ │ │ ▼ ▼ ▼ ┌──────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌─────────┐ │ V8 │ │ libuv │ │ Thread │ │(JS→ │ │(Schedules│ │ Pool │ │ Code)│ │ Tasks) │ │(Heavy │ └──────┘ └──────────┘ │ Work) │ └─────────┘ │ │ │ └─────────────────┼─────────────────┘ │ ▼ ┌──────────────────────┐ │ Operating System │ │ - File I/O │ │ - Network I/O │ │ - Process/Threads │ └──────────────────────┘ │ ▼ ┌─────────┐ │ CPU │ │(Machine │ │ Code) │ └─────────┘Key Insights:

-

V8 converts JavaScript to machine code, but it’s just one piece of the puzzle

-

Node.js is the orchestrator—it provides OS APIs and coordinates async execution

-

libuv manages concurrency—the thread pool, the event loop, timers, and I/O

-

The event loop is the heartbeat—phases determine when callbacks execute

-

Microtasks have priority—promises execute before timers

-

Thread pools scale with CPU cores—matching CPU cores to thread pool size for optimal throughput

-

Blocking is your enemy—the event loop is single-threaded for JavaScript, so CPU-heavy work must be delegated

-

Understanding this matters—it directly impacts whether your application is fast, responsive, and scalable

When You Find Yourself Debugging Performance Issues

Ask these questions:

- Is the event loop blocked? Check with flamegraphs or lag monitoring

- Is the thread pool saturated? Monitor

UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE - Are promises starving timers? Look for excessive microtask queueing

- Is there backpressure in streams? Check for memory leaks from buffering

- Is the work CPU-bound or I/O-bound? CPU-bound needs worker threads; I/O-bound benefits from async

These questions will guide you to the answer 90% of the time.

Further Reading

- Official libuv Documentation: http://docs.libuv.org/

- Jake Archibald on Event Loop: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCOL7MC4Pl0 (browser, but concepts apply)

- Node.js Source Code: https://github.com/nodejs/node

- Clinic.js for Profiling: https://clinicjs.org/

- Understanding Event Loop Lag: https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/blocking-vs-non-blocking/

Got questions? Found something wrong? Drop me a mail—I’d love to hear what resonates and what needs clarification.