The Hidden Layer: What LLMs Actually “See”

When you send this to an LLM:

"Hello, world! How are you?"The model never sees those characters. It sees this:

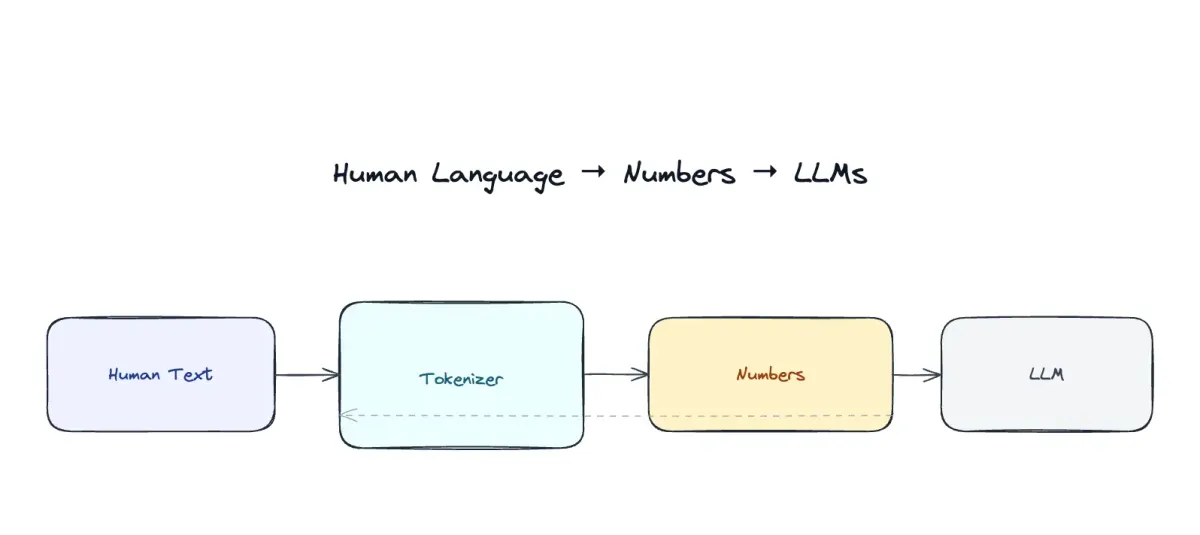

[1, 9906, 11, 1917, 0, 2650, 527, 499, 7673]Tokenizers are the translators. They convert human text into numbers that neural networks can process.

Human Text → Tokenizer → Numbers → LLM → Numbers → Tokenizer → TextWithout tokenizers, LLMs couldn’t work. Without understanding tokenizers, you can’t truly understand how LLMs work.

This post is about what happens in that first arrow.

Part 1: Why Tokenizers Exist

The Fundamental Problem

LLMs have a finite vocabulary. GPT-4 has ~100,000 tokens. Claude has ~100,000 tokens. These numbers are fixed at training time.

The number of possible texts in the world is infinite.

How do you represent infinite text with finite vocabulary?

Why Not Character-Level Tokenization?

Naive approach: Tokenize every character.

"hello" → [h, e, l, l, o] → 5 tokensProblem: This is inefficient.

- Explosion of tokens: A 100-page book becomes millions of tokens. More tokens = longer sequences = slower training and inference

- Loss of meaning: The model sees characters, not words or subwords. It has to learn that “h-e-l-l-o” means greeting

- Performance degradation: LLMs process tokens sequentially (transformers use attention). More tokens = quadratic computational cost. Doubling tokens = 4x more computation

Real comparison:

Character-level: "Hello, world!" = 13 tokensWord-level: "Hello, world!" = 3 tokensSubword-level: "Hello, world!" = 4 tokensCharacter-level loses. Every space, every punctuation becomes a token. Wasteful.

Why Not Word-Level Tokenization?

Better approach: One token per word.

"hello world" → ["hello", "world"] → 2 tokensProblem: Vocabulary explosion.

English has ~170,000 words. Add slang, names, typos, abbreviations, numbers, special characters, and you need 500,000+ tokens. Training becomes expensive. Storage becomes huge.

Also, what about “unhappily”? Is it one token or should it be split into [“un”, “happy”, “ly”] to capture structure?

The Goldilocks Solution: Subword Tokenization

Balance between character and word level.

"unhappily" → ["un", "happy", "##ly"] → 3 tokens"running" → ["run", "##ning"] → 2 tokens"hello" → ["hello"] → 1 token (common word)Subwords:

- Keep vocabulary manageable (~50,000 tokens)

- Reduce sequence length

- Preserve linguistic structure

- Handle unknown words

This is where Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) comes in.

Note

The Trade-off: BPE doesn’t magically solve the problem. It’s a compromise. Different languages, domains, and use cases need different tokenizers. GPT uses BPE. BERT uses WordPiece (similar idea). Others use SentencePiece.

Part 2: Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) Explained

The Core Idea

BPE is simple: Iteratively find the most frequent pair of tokens and merge them.

Example:

Initial text: “low w low w w” (broken into bytes/characters)

Iteration 1:"l o w w l o w w w w"Most frequent pair: "w w" (appears 3 times)Replace with new token "X":"l o X l o X X"

Iteration 2:"l o X l o X X"Most frequent pair: "o X" (appears 2 times)Replace with new token "Y":"l Y l Y Y"

Iteration 3:"l Y l Y Y"Most frequent pair: "l Y" (appears 2 times)Replace with new token "Z":"Z Z Y"You repeat this process, building a merge dictionary:

Merge 1: "w w" → token 256Merge 2: "o (token 256)" → token 257Merge 3: "l (token 257)" → token 258After N merges, you have a vocabulary of 256 (base bytes) + N (merges). If N = 50,000, vocabulary = 50,256.

Why BPE Works

- Frequency-based: Common sequences get their own tokens. “the”, “ing”, “ed” become single tokens

- Rare sequences stay split: Uncommon combinations remain as character sequences

- Handles unknown words: Any word, no matter how rare, can be tokenized by its subwords

- Data-driven: The merge dictionary is learned from training data, capturing language-specific patterns

Part 3: Implementing a Tokenizer

Step 1: Start With UTF-8 Bytes

const str = "Hello, world!";const bytes = [...Buffer.from(str, 'utf-8')];// bytes = [72, 101, 108, 108, 111, 44, 32, 119, 111, 114, 108, 100, 33]// (H, e, l, l, o, , , w, o, r, l, d, !)Every character is now a number (its UTF-8 byte value).

Step 2: Find Most Frequent Pair (getPairStats)

function getPairStats(data: number[]) { const stats: Record<string, number | undefined> = {}

// Count all adjacent pairs for (let i = 0; i < data.length - 1; i++) { const pair = `${data[i]}-${data[i + 1]}`; stats[pair] = (stats[pair] ?? 0) + 1; }

// Return sorted by frequency (highest first) return [...Object.entries(stats)] .map(([pair, count]) => [count, pair.split('-').map(Number)]) .sort((a, b) => b[0] - a[0]);}This counts adjacent byte pairs and ranks them by frequency.

Example:

bytes = [72, 101, 108, 108, 111, ...]Pairs: 72-101: 1 time (H-e) 101-108: 1 time (e-l) 108-108: 1 time (l-l) 108-111: 1 time (l-o) ...If a pair appears multiple times, it gets a higher count.

Step 3: Merge the Most Frequent Pair (performTokenSwapping)

function performTokenSwapping({ tokens, mergePair, newTokenId}) { let result = [...tokens];

// Find and replace all instances of mergePair for (let i = 0; i < result.length - 1; i++) { if (result[i] === mergePair[0] && result[i + 1] === mergePair[1]) { result[i] = newTokenId; // Replace with new ID result[i + 1] = null; // Mark for deletion } }

// Remove nulls return result.filter(t => t != null);}If the most frequent pair is (108, 108) — “ll” — you replace it with token ID 256.

Before: [108, 108, 111] (l, l, o)After: [256, 111] (ll, o)Step 4: Repeat Until Target Vocabulary Size

const sizeOfVocab = 300; // Target vocabulary sizeconst iterationsRequired = sizeOfVocab - 256; // 44 iterations

// Start with 256 base tokens (0-255 are UTF-8 bytes)// Perform 44 merges to reach 300 tokens totalfor (let i = 0; i < iterationsRequired; i++) { const mostFrequentPair = getPairStats(tokensToOperateOn)[0][1]; const newTokenId = 256 + i;

tokensToOperateOn = performTokenSwapping({ tokens: tokensToOperateOn, mergePair: mostFrequentPair, newTokenId });

mergeDictOrdered.push([`${mostFrequentPair[0]}-${mostFrequentPair[1]}`, newTokenId]);}After 44 iterations, you have 300 unique tokens and a merge dictionary.

Step 5: Encoding (Text → Tokens)

function encode(str: string) { let bytes = [...Buffer.from(str, 'utf-8')];

// Apply merges in order for (const [pair, newTokenId] of mergeDictOrdered) { const [b1, b2] = pair.split('-').map(Number);

// Replace all occurrences of this pair for (let i = 0; i < bytes.length - 1; i++) { if (bytes[i] === b1 && bytes[i + 1] === b2) { bytes[i] = newTokenId; bytes[i + 1] = null; i++; // Skip next byte (now null) } } }

return bytes.filter(t => t != null);}When you encode new text, you apply the merge dictionary in order of priority.

Example:

Text: "hello"Bytes: [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]

If merge 1 was (108, 108) → 256:After merge 1: [104, 101, 256, 111]

If merge 2 was (256, 111) → 257:After merge 2: [104, 101, 257]

If merge 3 was (101, 257) → 258:After merge 3: [104, 258]

Final tokens: [104, 258]Step 6: Decoding (Tokens → Text)

function decode(tokens: number[]) { const bytes = [...tokens];

// Build reverse dictionary const reverseDict = {}; for (const [pair, newTokenId] of mergeDictOrdered) { const [n1, n2] = pair.split('-').map(Number); reverseDict[newTokenId] = { n1, n2 }; }

// Undo merges in reverse order for (let i = 0; i < bytes.length; i++) { const lookup = reverseDict[bytes[i]]; if (lookup) { bytes[i] = lookup.n1; bytes.splice(i + 1, 0, lookup.n2); i--; // Re-check this position } }

// Convert back to UTF-8 string return Buffer.from(bytes).toString('utf-8');}To decode, reverse the merges. Split each merged token back into its components.

Tokens: [104, 258]

If merge 3 was (101, 257) → 258:After reverse: [104, 101, 257]

If merge 2 was (256, 111) → 257:After reverse: [104, 101, 256, 111]

If merge 1 was (108, 108) → 256:After reverse: [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]

Convert to string: "hello"Note

Key insight: The merge dictionary is deterministic and the same across encoding and decoding. Without it, you couldn’t decode tokens back to text. This is why tokenizers are shipped with models—each model has its own dictionary.

Part 4: Real-World Complexity

Above implementation is clean and educational. Real tokenizers add complexity:

1. Special Tokens

Real tokenizers have special tokens:

<PAD>: Padding (fills sequence to fixed length)<UNK>: Unknown (rare tokens not in vocabulary)<BOS>: Beginning of sequence<EOS>: End of sequence<MASK>: For masked language modeling (BERT)

2. Normalization

Before tokenizing, text is normalized:

- Lowercasing (optional)

- Accent removal: “café” → “cafe”

- Whitespace handling: Multiple spaces → one space

3. Pre-tokenization

Many tokenizers split on whitespace first:

"Hello, world!" → ["Hello", ",", "world", "!"]Then tokenize each part separately. This prevents merging across word boundaries (usually desired).

4. UTF-8 Encoding Issues

This code uses UTF-8 bytes directly. Real tokenizers handle edge cases:

- Multi-byte UTF-8 sequences (emojis, CJK characters)

- Invalid UTF-8 sequences

- Different byte order marks

The test string handles this well:

"José" (é is 2 bytes in UTF-8)"世界" (each character is 3 bytes)"👋🚀" (each emoji is 4 bytes)The tokenizer correctly processes all of this!

5. Vocabulary Size Trade-offs

Smaller vocabulary (256): Longer sequences, faster training, less memoryLarger vocabulary (100k): Shorter sequences, slower training, more memoryReal models balance this. GPT-3 uses 50,257 tokens. Optimal for English but not for CJK languages.

Note

Important: LLMs can’t “exhaustively” tokenize every possible string. If you use a token ID that wasn’t in the merge dictionary, the model doesn’t know how to interpret it. This is why OOV (out-of-vocabulary) handling matters. Real tokenizers map unknown tokens to <UNK> or break them into subword pieces.

Part 5: Why Tokenizers Matter for Performance

Token Count Explosion

The compression from your tokenizer is dramatic:

console.log('Original:', bytes.length); // 500 bytesconsole.log('Final:', tokensToOperateOn.length); // Maybe 150 tokensWhy this matters:

Original bytes: 500 characters = 500 tokens (character-level)BPE tokens: 150 tokens (subword-level)Compression: 3.3x fewer tokens

Impact:- Memory: 500 tokens requires more GPU memory to process- Speed: Attention is O(n²), so 500 tokens = 250,000 attention operations 150 tokens = 22,500 attention operations- Inference: Fewer tokens = faster inferenceThis is why subword tokenization is crucial for LLM efficiency.

Context Window Trade-off

An LLM has a context window (max tokens it processes):

- GPT-3: 4,096 tokens

- GPT-4: 128,000 tokens

- Claude 3: 200,000 tokens

With character-level tokenization, a 4K context window only fits 4,000 characters (1-2 pages). With BPE, it fits ~12,000 characters (4-5 pages).

Part 6: Comparison: BPE vs. Other Tokenization Methods

WordPiece (BERT, RoBERTa)

Similar to BPE but merges based on likelihood, not frequency.

BPE: Most frequent pairWordPiece: Pair that maximizes likelihoodSlightly better quality, slightly slower to train.

SentencePiece (ALBERT, MT5)

Language-agnostic tokenization. Trains on raw bytes, handles any language equally.

Better for multilingual models but slightly less interpretable.

Tiktoken (OpenAI)

GPT’s tokenizer. Optimized specifically for GPT models.

- Regex-based pre-tokenization

- Better handling of whitespace and special characters

- Proprietary but open-sourced

Part 7: Limitations and Considerations

1. Tokenizer-Model Mismatch

If you train a model with one tokenizer and deploy with another, outputs break.

Training tokenizer: "hello" → [123, 456]Deployment tokenizer: "hello" → [789, 101]Result: Model reads wrong tokens, produces garbageThis is why tokenizers are versioned with models.

2. Tokenization Artifacts

Some text gets tokenized weirdly:

"123" might tokenize as [1, 2, 3] (digit-by-digit) depending on training dataThis hurts the model's ability to understand numbersGPT learned to handle this by training on code (which has numbers), but other models struggle.

3. Non-Reversible Tokenization

Some tokenizers lose information:

Original: "HELLO"Lowercased: "hello"Tokenized: [123]Decoded: "hello" (case lost)Above implementation is fully reversible, but real tokenizers often aren’t (by design, for normalization).

4. Inefficient Tokenization for Certain Languages

CJK languages (Chinese, Japanese, Korean) tokenize poorly with BPE:

English: "hello world" = 2 tokensChinese: "你好世界" = might be 4+ tokens (each character separate)This is why multilingual models need better tokenizers.

Part 8: How Real LLMs Use Tokenizers

Training Phase

Raw text → Tokenizer → Token IDs → Embedding Layer → TransformerThe tokenizer is part of the data pipeline. Every epoch, raw text is re-tokenized.

Inference Phase

User input → Tokenizer → Token IDs → Model → Token IDs → Detokenizer → TextThe same tokenizer used during training is used during inference. This is why tokenizer version matters.

Streaming (Like ChatGPT Web Interface)

User input → Tokenize → Stream through model → Stream token outputs → Detokenize to textTokens are decoded one-by-one as they’re generated, creating the “typing” effect.

Part 9: Conclusion: Tokenizers Are Bridges, Not Details

Tokenizers are often overlooked. They’re not “interesting” like transformer attention or reinforcement learning.

But they’re fundamental. They’re the bridge between human language and machine numbers.

Understanding tokenizers helps you understand:

- Why LLM context windows are limited (tokens, not characters)

- Why multilingual models struggle (unbalanced tokenization across languages)

- Why certain tasks are easier (more tokens = more signal to the model)

- Why different models behave differently (each has its own tokenizer)

- How to debug model outputs (understanding tokenization artifacts)

This is what powers GPT, Claude, Gemini. The core algorithm is simple. The engineering is elegant.

The next time you interact with an LLM, remember: your text is being converted to numbers by a tokenizer. Understanding that process is understanding the foundation of how LLMs work.