The Problem: How Do We Connect Multiple Video Streams?

Imagine you’re building a video conference app. Two people need to see and hear each other.

Easy: Direct connection. No server needed.

Now add 10 more people. Now 100. Now 1000.

Hard: How do you route video streams between all of them efficiently?

This is where WebRTC architectures come in. Different designs solve this problem in different ways, each with trade-offs.

Part 1: The Simplest Solution — Peer-to-Peer (P2P)

Direct Connection Between Two Peers

In WebRTC, a peer is simply a user. When two peers communicate directly, they establish a connection without any server in between.

User A ←→ User B(WebRTC over UDP)How it works:

- User A and User B exchange SDP (Session Description Protocol) offers

- WebRTC establishes a direct UDP connection

- Video/audio streams flow directly between them

- No server, no latency from routing through infrastructure

Advantages:

- Minimal latency (direct connection)

- No server cost

- Privacy (data doesn’t pass through third parties)

- Simple to implement

Disadvantages:

- Only works for 2 people

- Not scalable

- Requires NAT traversal (STUN/TURN servers, but not for relaying)

Note

WebRTC Basics: WebRTC uses UDP instead of TCP because video calls prioritize speed over reliability. A dropped frame is acceptable; retransmitting it would increase latency. UDP is connectionless, fast, and perfect for real-time communication.

Part 2: Adding More Peers — The Mesh Problem

What Happens When a 3rd Peer Joins?

Now User C wants to join the call. User C needs to connect with both User A and User B.

User A / \ / \User B -- User CEach peer sends its stream to every other peer. This is called mesh P2P architecture.

The Mesh Topology

In a mesh network:

- Every peer connects to every other peer

- Each peer sends its stream N-1 times (where N = total peers)

- Each peer receives N-1 streams

4 peers = 6 connections:

User A ↔ User BUser A ↔ User CUser A ↔ User DUser B ↔ User CUser B ↔ User DUser C ↔ User DMathematical formula: For N peers, connections = N × (N-1) / 2

2 peers: 1 connection3 peers: 3 connections4 peers: 6 connections5 peers: 10 connections10 peers: 45 connections20 peers: 190 connectionsWhy Mesh Fails

1. Bandwidth explosion:

Each peer must upload its stream to N-1 peers. If each stream is 2 Mbps:

10 peers: Each peer uploads 2 × 9 = 18 Mbps20 peers: Each peer uploads 2 × 19 = 38 MbpsYour home internet might not support this.

2. CPU intensive:

Encoding multiple streams simultaneously is CPU-heavy. Your laptop’s processor maxes out.

3. Not fault-tolerant:

If one peer drops, the connection graph breaks. You need to reconnect everyone.

4. Terrible for mobile:

Battery drain from continuous upload. Data usage is astronomical.

Solution: We need a server to centralize connections.

Note

Mesh is only practical for very small groups (2-4 people). Anything larger needs a central server. This is why P2P video calls are limited to 1-on-1; group calls need infrastructure.

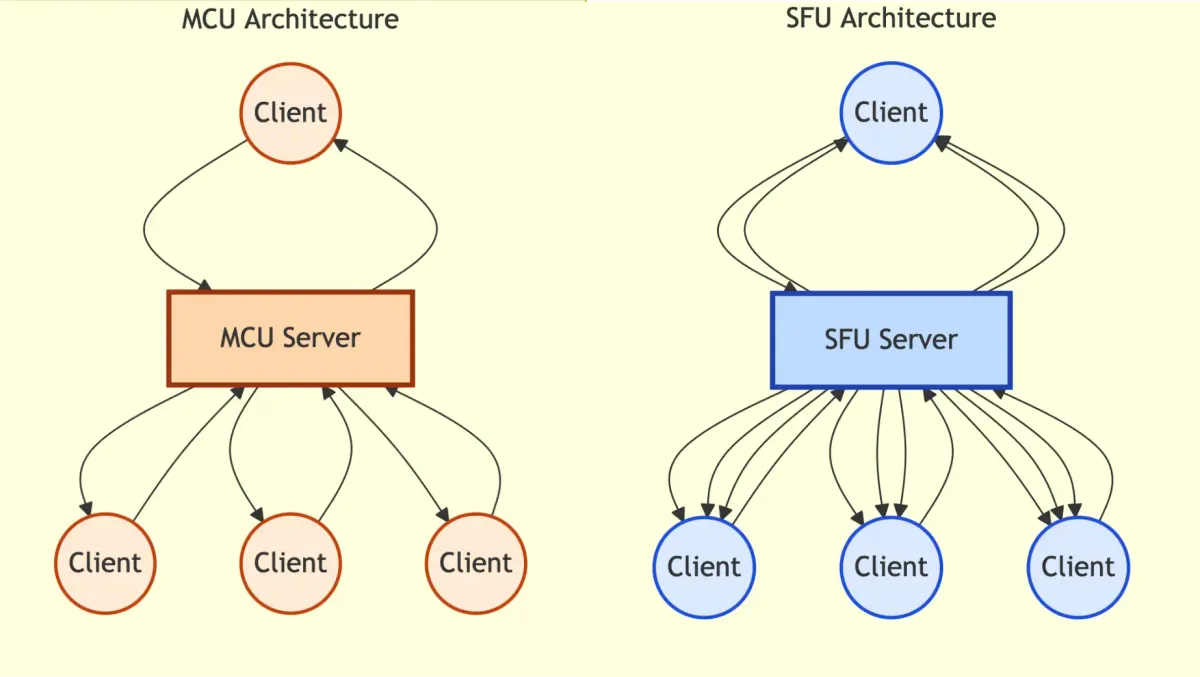

Part 3: Introducing a Server — MCU (Multipoint Control Unit)

Centralized Mixing

Instead of mesh, introduce a server in the middle:

User A \User B → MCU Server → [Mixed Stream] → All UsersUser C /The MCU (Multipoint Control Unit) is a server that:

- Receives streams from all peers

- Mixes them into a single video (like a video grid)

- Broadcasts the mixed stream to all peers

How MCU Works

Imagine a grid of 4 video tiles:

[User A] [User B][User C] [User D]The MCU:

- Receives raw streams from User A, B, C, D

- Resizes and arranges them into a grid

- Composes them into a single video output

- Encodes and sends the same video to all users

Advantages of MCU

- Bandwidth efficient (each peer uploads once, downloads once)

- Scalable (server handles mixing)

- Simple for clients (receive one stream, display it)

Disadvantages of MCU

- CPU intensive: Real-time video mixing/compositing is expensive

- High latency: Processing multiple streams, composing, encoding = delays. Lag is noticeable

- Expensive to run: Server costs scale with processing power

- Inflexible: Fixed layout. If one user goes fullscreen, everyone sees the same stream. You can’t show different content to different users

- Quality loss: Compositing often reduces quality to save CPU

Real example: Old WebEx systems used MCU. Noticeable lag and visual artifacts.

Note

The Compositing Problem: Combining multiple video streams in real-time is non-trivial:

- Resize each stream to fit the grid

- Blend them together

- Re-encode the output

- All in under 33ms (for 30fps video)

This is why MCU requires powerful servers.

Part 4: The Better Approach — SFU (Selective Forwarding Unit)

No Mixing, Just Forwarding

SFU is an evolution of MCU that solves the mixing problem by… not mixing at all.

User A → \User B → → SFU Server → [Stream A, Stream B, Stream C, Stream D] → All UsersUser C → /The SFU (Selective Forwarding Unit):

- Receives streams from all peers (like MCU)

- Does NOT mix them (unlike MCU)

- Forwards raw streams to all peers

- Lets the client decide how to render

How SFU Works

Instead of sending a single mixed video:

SFU → User A: [Stream B, Stream C, Stream D]SFU → User B: [Stream A, Stream C, Stream D]SFU → User C: [Stream A, Stream B, Stream D]SFU → User D: [Stream A, Stream B, Stream C]Each peer receives raw video streams from every other peer and arranges them client-side.

The client decides:

- How to layout the grid

- Which video to highlight

- Which streams to mute

- Which stream to display fullscreen

Advantages of SFU

1. Low latency: No mixing = minimal processing. Just forward streams. Latency is much lower than MCU.

2. Flexible rendering: Each user sees what they choose. User A can fullscreen User B while User C sees everyone in grid mode.

User A's screen: [User B fullscreen]User C's screen: [Grid: A, B, C, D]Different clients, different layouts3. Easy to mute: Want to stop seeing User B? Client simply stops downloading their stream.

4. Scalable: Server doesn’t do heavy processing. It’s basically a smart router. More CPU = more users.

5. Efficient bandwidth: Each peer uploads once. Downloads scale with group size, but that’s the same for all architectures. Benefit: only download what you need.

Disadvantages of SFU

- More bandwidth for clients: Each client receives multiple streams (one per peer). Download = N-1 streams

- Client-side processing: Decoding and rendering multiple streams uses CPU on your device

- Network congestion: If a peer has poor upload, it affects everyone (they receive a poor-quality stream)

Trade-off: SFU moves work from server to clients. Servers are more powerful, but clients distribute the load.

Part 5: Comparing the Three Architectures

| Aspect | Mesh P2P | MCU | SFU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connections per peer | N-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bandwidth per peer | High | Low | Medium-High |

| Server processing | None | Very High | Low |

| Latency | Lowest | Highest | Low |

| Scalability | Poor | Medium | High |

| Flexibility | High | Low | High |

| Cost | Low | High | Medium |

| Best for | 1-1 calls | Small groups with fixed layout | Large groups |

Part 6: Real-World Examples

Zoom

Zoom primarily uses SFU architecture.

Why?

- Handles 1000+ participants (scalable)

- Low latency (you can see people react in real-time)

- Flexible UI (you choose gallery view, spotlight, fullscreen)

- Server is a router, not a processor

When you’re in a 100-person Zoom call, the server isn’t composing a 100-person grid. It’s forwarding 100 separate video streams.

Google Meet

Google Meet uses SFU with some hybrid elements.

- Large meetings: SFU (everyone receives multiple streams)

- For display, sometimes uses client-side layout (no MCU mixing)

Teams/Skype

Microsoft uses SFU for most calls, with MCU for specific scenarios (like recording entire meeting as one video).

Discord/Telegram

Small group calls: SFU (Discord supports up to 25 people on video)

Why not larger? Because receiving 25 streams stresses home internet.

Part 7: When Do You Use Each?

Use Mesh P2P When:

- Only 2 people (1-on-1 calls)

- Privacy is critical (no server involvement)

- Low latency is essential

- You have good internet

Example: Secure peer-to-peer chat apps, some P2P game networking.

Use MCU When:

- Small group (3-10 people)

- Fixed layout is acceptable

- You want to save client bandwidth

- Recording the entire call as one video

Example: Traditional conference systems, old WebEx/Polycom.

Use SFU When:

- Large groups (10+ people)

- Flexible UI is important

- Low latency is critical

- Scalability matters

Example: Zoom, Google Meet, modern conferencing platforms.

Part 8: The Client Rendering Problem

In SFU, clients receive multiple streams. Now the client must:

- Decode each stream (video codec, like VP8 or H264)

- Resize each stream to fit the grid

- Compose them into a canvas

- Render at 30fps

This is CPU-intensive. Here’s why Zoom on a laptop can get hot:

10 participants × 30fps × decoding overhead = High CPU usageOptimization: Clients often:

- Reduce resolution of non-focal streams (you don’t need 4K for a small tile)

- Pause decoding of streams you’re not looking at

- Use hardware acceleration (GPU) for video decoding

Part 9: Conclusion: Architecture Affects Everything

The architecture you choose isn’t just technical. It affects:

- Latency: How fast do users see reactions?

- Scalability: How many people can join?

- Cost: How much does the server cost?

- Quality: What resolution and framerate?

- User Experience: Can I mute someone? Go fullscreen? Control my view?

The trend: Modern platforms use SFU because:

- Scales better than MCU

- Lower latency than MCU

- Better UX than P2P

- Cost-effective